Canal Archaeology

The development of Pennsylvania's canal system began in the early 1800s. Financed largely by the Commonwealth's General Assembly, by 1834 over 600 miles of canal and 125 miles of auxiliary railroad were opened between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Significant engineering achievements included the Columbia-Philadelphia and Allegheny Portage railroads that transported canal boats over land between canals. Canal boats carried passengers, coal, farm produce, lumber, and other raw materials from rural and outlying areas to urban areas. Often they returned to less developed areas with manufactured goods. The canals spurred economic growth, providing employment for boat-builders, boatmen, and teamsters. They also stimulated development of manufacturing industries, provided access to markets for raw materials and agricultural goods, and spawned service industries such as inns, taverns, and stores.

Large amounts of earth (over 80 million tons) were removed to build Pennsylvania's canal system and thousands of immigrants found employment in its construction. Canal boatman, lock tenders, suppliers, and many others earned livings in the canal industry. However, while canals stimulated economic development and provided jobs, the canal system itself proved unsuccessful in the long term. Competition from railroads and declining public and private investment in canal construction and maintenance led to their decline by the 1850s. Census data demonstrate a precipitous population decline in canal towns such as Liverpool and New Buffalo, and entire ways-of-life soon disappeared.

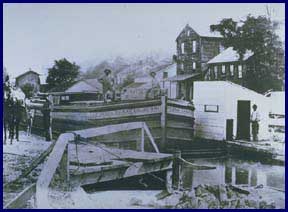

A canal barge

Archaeological investigations have revealed intriguing findings along many sections of the Delaware, Susquehanna, and Ohio River canal systems and at many canal-related sites. For example, as part of the widening of State Routes 11 and 15, an inventory of the Susquehanna Division of the Pennsylvania Canal was conducted by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT). Canal-related resources such as locks, aqueducts, culverts, and lock-tender's houses were identified in the 27 miles of survey.

Remaining walls of a canal lock on the Susquehanna Division

Additionally, construction of Interstates 279 and 579 in Pittsburgh uncovered a canal basin and locks that included preserved wood and numerous leather items. One conclusion drawn from such archaeological investigations is that canals required a great deal of maintenance. For example, clay linings that held water in canal basins frequently eroded and filled with silt. Evidence of constant maintenance demands adds to contemporary interpretations of the challenges evident in this once-popular mode of transportation.

Another significant conclusion of canal archaeology is that numerous businesses emerged near these manmade waterways. Not unlike modern day fast food businesses that cater to travelers on America's interstate highways, many towns adjacent to canals featured taverns, hotels, merchants, and other businesses that catered to those associated with the canal industry. A key example is the Gayman Tavern in Dauphin County. PennDOT sponsored investigations at the tavern as part of the State Routes 22 and 322 widening project. The investigations uncovered over 42,000 artifacts, including bone and plant remains. The remnants of five outbuildings and nine privies were also uncovered. As with most privies, these were commonly used as trash dumps and thus revealed artifacts such as animal bones and broken dishes. Bone recovered in the excavations indicated that the most common types of meat dishes served at the tavern were sliced ham, beef steak, and a variety of stews - meals easily prepared for customers. Tableware was not of the highest quality, but customers were probably more interested in the quality of the food than the plates. A doll's head suggested the presence of children in the Gayman household. This is not a surprising artifact find, although a comparison with 21st century fast food stores would demonstrate many more toys, emphasizing that modern business of this type cater to children. In sum, the tavern served as a place for rest, refreshment, and exchange of news during the heyday of canals. And when the canal closed, so did the doors of Gayman Tavern.