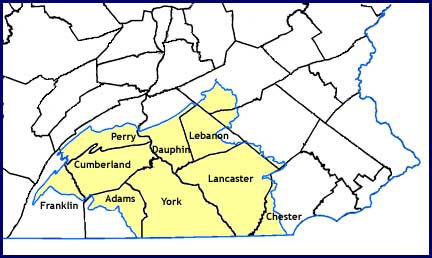

Lower Susquehanna River Basin

The subbasin includes all of York, Lancaster, and Cumberland Counties, and parts of Perry, Dauphin, Lebanon, Chester, Adams, Berks, and Schuylkill Counties. The region consists of rolling valley floor cut by small streams. Major tributaries of the Susquehanna River include Conodoguinet Creek, Yellow Breeches Creek, Codorus Creek, Pequea Creek, and the Conestoga River. The major research in this region has been conducted by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, which has been working here since the 1930s. Franklin and Marshall College has also conducted research in the subbasin and most recently has conducted historic archaeology in Lancaster.

Approximately 2,865 archaeological sites are recorded in the Lower Susquehanna River Subbasin. Of these, 1,188 can be dated to specific prehistoric time periods and 174 to specific historic time periods.

The Paleoindian Period

The Paleoindian period represents the earliest occupation of the region, during which the Lower Susquehanna River Subbasin was sparsely occupied by small groups of foragers. The climate was evolving from Ice Age conditions and plants and animals were very different in the Lower Susquehanna than they are today.

Twenty-four Paleoindian sites have been recorded in the subbasin, 13 of which are in Lancaster County. A cluster of five sites is located along the Susquehanna River in Washington Boro. These sites probably represent repeated visits by extended family groups. Their tools were made from local quartz but also from jasper, an iron rich stone that could have originated from Berks County or from the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. A Paleoindian site in the Upper Conestoga drainage was excavated and revealed tools and flakes of jasper. Because few tools were found, the site was interpreted as a special purpose site, possibly related to hunting and butchering.

Early and Middle Archaic Periods

During the Early and Middle Archaic periods people lived in small groups, moving their camps frequently to hunt, fish, and gather wild plant foods. Territories were somewhat smaller. The climate and vegetation gradually took on its modern characteristics by Middle Archaic times.

There are 225 recorded Early and Middle Archaic sites in the subbasin, but few have been excavated. Most of the sites are surface finds with a small number of artifacts. The cold climate of the glacial period continued to warm, and oak, which provides food for both humans and the deer they hunted, was an increasingly important part of the forest. Surveys suggest that Early Archaic sites are most often located near bogs and swamps, areas that are attractive to game. Middle Archaic sites are often found near seasonal streams and springs or adjacent to floodplains. City Island in Harrisburg is one of the few excavated sites from this time period. A spear point and a small hearth date the occupation to over 8000 years ago. It appears to have been occupied by small nuclear family-sized groups.

Late Archaic and Transitional Periods

Population density increased during the Late Archaic and Transitional Periods. Groups of related families established base camps, which they moved less frequently than in earlier periods. Transitional period sites contain evidence for the intensive processing of food resources in the form of large roasting pits and/or stone boiling pits. Carved stone bowls are first used at this time and represent the first portable cooking containers. There is some evidence for a change in climate in the form of a warm, dry period, which may have been a motivation behind the changes. Trade and burial ceremonialism are suggested throughout eastern Pennsylvania.

Over 750 sites have been recorded for the drainage, which is a significant increase over Early and Middle Archaic times. Several significant sites have been excavated. Two of the earliest archaeological investigations took place at sites on Susquehanna River islands: the Kent-Hally Site on Bare Island and the Piney Island Site. Both had layered sequences of Late Archaic and Transitional Period occupations with stemmed spear points and broadspears. Other artifacts recovered on the islands included drills, ground and polished tools such as axes and celts, and rough stone tools such as mullers, pestles, and milling stones, used for grinding nuts and seeds. More recent excavations on Calver Island recovered similar artifacts and a large number of fire pits, roasting pits, and scatters of fire-cracked rock. These sites indicate that islands were an important part of the hunter-gatherer settlement system. The extensive work at the City Island site also revealed a large Late Archaic base camp consisting of a wide variety of tools and numerous cooking hearths.

These sites also contained broken fragments of stone bowls made of a soft stone known as soapstone or steatite. These containers are found in a variety of sizes, and some were large and obviously used in cooking. However, some are relatively small, holding less than a quart of liquid and their function is problematic. Steatite in Pennsylvania is only found in eastern Lancaster County. However, it was traded, probably using dugout canoes, all over the Susquehanna, Delaware, and Ohio Valleys.

Late Archaic and Transtional Period artifacts from Calver Island

Early and Middle Woodland Period

The Early and Middle Woodland periods in the Lower Susquehanna subbasin are not well understood because few sites from these periods have been found. People began using pottery and probably stayed in one place for longer periods. They continued to hunt and gather for their food resources but there is some evidence that they began to intensify their exploitation of plant foods.

Only 170 sites from the Early and Middle Woodland periods have been recorded in the subbasin. The distribution of sites is similar to that of the Late Archaic Period. Although base camps with house features have been identified elsewhere in the Middle Atlantic region, none has been found in the Lower Susquehanna River subbasin. Thus, the Early Woodland and Middle Woodland are among the most poorly understood periods of prehistory in this region. The Three Mile Island site represents one of the few excavated sites from this time period.

Late Woodland Period

The> Late Woodland marks beginning of village life, a reliance on agriculture, and the widespread use of improved pottery.

Approximately 406 Late Woodland archaeological sites have been identified. They are recognized by pottery with incised decorations in geometric patterns. Late Woodland cultural succession is better known in the Lower Susquehanna Valley than practically anywhere else in the state. The first Late Woodland culture in the valley is known as Shenks Ferry and several sites have been excavated. It would appear that these people were the first farmers in the region. They initially lived in small hamlets but by AD 1400 they began to concentrate into large villages with wooden walls or stockades. One of the earliest stockaded villages was the Murry Site, a four-acre village along the Susquehanna River that dated to about 1400 A.D. The excavations revealed evidence of 52 houses, indicating that the village population was between 300 and 500 people. The houses were laid out in two concentric rings surrounding a large, central structure believed to be a communal or ceremonial structure. More recent excavations at the Slackwater Site, located in the Conestoga River drainage near Millersville, produced similar radiocarbon dates but a much less organized village plan. The Commonwealth's Archaeology Program is currently excavating a Late Woodland village at the Quaker Hills Quarry site near Millersville. This site is as large as the Murry site but dates to AD 1500 and represents one of the latest large Shenks Ferry villages.

The Shenks Ferry culture seems to disappear with the appearance of people known as the Susquehannocks. These were Iroquoian speakers, and they are known from both extensive historic and archaeological research. These were large scale agriculturalists who moved their villages approximately every twenty years as they depleted the nutrients in the soil.

The Susquehannocks established large fortified villages along the Susquehanna River in Lancaster and York Counties beginning in AD 1525. One of their earliest forts is the Schultz Site, which contained longhouses up to 95 feet in length that were probably occupied by related families. Excavations at the Strickler and Washington Boro Village Sites produced middens (layers of trash) with charred corn cobs and fragments of pumpkins and squash with attached masses of seeds. A wide variety of animal bones with butchering marks was also found.

The Susquehannocks engaged in extensive fur trading with the English, Dutch, and Swedes, receiving goods such as glass beads, iron axes, metal harpoons, brass kettles and flintlock muskets. Although, they controlled the fur trade for nearly a century, they were in constant conflict with other Indian tribes, especially the Seneca of western New York State. Large scale battles took place with the Seneca in Washington Boro and across the river in York County. Warfare and disease eventually caught up with the Susquehannocks, and in 1675, approximately 500 survivors sought refuge with the English in Baltimore. However, this arrangement also ended in disaster, and with permission of the Seneca, they soon returned to the Lower Susquehanna Valley. They became known as the Conestoga Indians and frequently worked as laborers on local farms. Two weeks before Christmas, in 1763, they were attacked by a gang from Harrisburg known as the "Paxtang Boys," who were upset by Indian attacks from the Ohio Valley. The survivors were placed in the Lancaster jail for their own protection but two days after Christmas, the Paxtang Boys returned and killed every man, woman, and child, thus ending the Susquehannock culture.

Schematic site plan of the Murry Site

Historic Period

The Historic Period followed European contact with Native Americans in the Lower Susquehanna River drainage.

Over 150 historic sites, most of which are houses and farmsteads, are recorded in the subbasin.

Two important historic sites are military: the Carlisle Barracks and Camp Security. Carlisle Barracks is a US Army educational facility that was founded in 1757 and first used to train soldiers to fight Native Americans. A management plan for archaeology has been developed, and detailed the procedures to be used when ground-disturbing activities are undertaken at the Barracks.

Camp Security was a Revolutionary War prison camp for British prisoners and their families. Limited archeological excavations revealed pewter buttons, coins dating to as early as 1744, and musket balls. Much more remains to be learned about the site, which is in danger of destruction from modern development.

Ephrata Cloister

The State Museum of Pennsylvania has done extensive archaeological excavations at Ephrata Cloister, an eighteenth-century community of celibate brothers and their supporters. Excavations between 1993 and 1998 uncovered findings that contradicted historical information. For example, kitchen refuse contained butchered animal bone despite historical information that the occupants were vegetarians. The most unexpected find was a nearly complete hand-blown glass trumpet, an expensive instrument likely imported from the Old World and out of place in a community based on vows of poverty.

Glass trumpet in situ, Ephrata Cloister