Residential Institutions

The Industrial Revolution and its attendant increase in urban population amplified certain social problems, providing religious groups with great impetus to address them. As Walter Rauschenbusch, a critic of the impact of industrialization on the workers and one of the leaders of the "Social Gospel" movement [1], commented in Christianity and the Social Crisis:

We point with great pride to our charitable organizations. These institutions are the pride and shame of Christian civilization; the pride because we respond to the cry of suffering; the shame, because so much need exists [2].

In addition, discussing Protestant evangelizing efforts in urban areas, Anne M. Boylan, in her Sunday School: The Formation of an American Institution, 1790-1880 [3] notes that:

These efforts familiarized Protestant activists with the conditions that prevailed in large urban centers and led them to experiment with a variety of palliatives. Mission chapels, asylums for the aged and orphaned, neighborhood prayer meeting, charity schools, urban revivals, missions for sailors and other groups, home visitation, and Sunday schools all found their way into the arsenal of weapons evangelical protestants used to attack poverty and irreligion (emphasis added).

Orphanages

According to Nurith Zmora's Orphanages Reconsidered: Child Care Institutions in Progressive Era Baltimore, the societal problems that accompanied the Industrial Revolution and urbanization - from poverty to epidemic disease to workplace accidents - led to an explosion in the number of orphanages in the United States. Prior to about 1830, the United States boasted just over 20 orphanages in total. Between 1831 and 1851, that number almost quadrupled, jumping to 77 total [4]. Furthermore, of the orphanages established, 9 out of 10 were private, with Catholic orphanages making up the largest percentage with 54 percent [5]. As mentioned for other social institutions (such as schools), the association between this type of institution and a particular religious group may not be readily apparent from the exterior or interior finishes; the function of the property dictated its form. These institutions may be part of a larger religious complex (e.g. in association with a convent or other religious structure), they may comprise a stand-alone complex, or they may adaptively re-use older historic buildings. (Before founding Cabrini College on the Paul estate, the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus used it to house an orphanage, for example.) In addition, their religious (and sometimes ethnic) connection may only be apparent in their name or in historic documentation. As mentioned for educational institutions, the name St. Stanislaus would likely indicate an association with the Polish.

St. Stanislaus Institute

Location:

141 Old Newport Street, Newport Township, Luzerne County

National Register Status:

Listed (12/30/2008)

Description:

Founded in 1918 by the Scranton Diocese, this Catholic orphanage served the Polish Catholic community until 1972. The complex consists of 6 buildings: the boys' dormitory (1918), the girls' dormitory (1924), the Holy Child Chapel (1939), the laundry/boiler house (1939), the rectory (1924), and the rectory garage (1924).

Topton Lutheran Home

Location:

1 Home Avenue, Longswamp Township, Berks County

National Register Status:

While the entire complex is ineligible (6/18/2010), Old Main is eligible for its architecture (6/18/2010).

Description:

Founded in 1896 by the Berks County Sunday School Association, this facility, which has served the Lutheran community in Berks and the surrounding counties of Lehigh and Montgomery up to the present, was originally an orphanage. In 1940, the home added eldercare to its mission; in 1970, it added the "Family Life Services Division." The complex, which, when purchased, was a working farm and which incorporated the earlier farm resources (even using the farmhouse as the original orphanage) consists of 16 resources: the original farmhouse (ca. 1813), a barn (ca. 1920), the orphanage building (ca. 1899), an infirmary building (ca. 1911) (later used as an old age home), the Allentown Conference Cottage (ca. 1926) (used as a cottage for boys), an auditorium (ca. 1939) (used for classrooms, gym, and auditorium), Krum Memorial Cottage (ca. 1949) (housed the superintendent and his family), the H.H. Gilbert Memorial Building (ca. 1952) (used as a maintenance building and office), as well as numerous modern buildings built as the facility grew and its mission expanded.

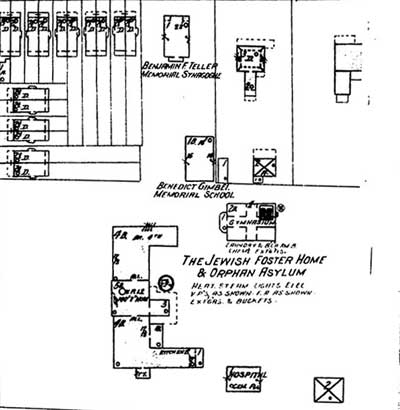

Jewish Foster Home and Orphan Asylum

Location:

700 E. Church Lane, Philadelphia

National Register Status:

Undetermined

Description:

Founded primarily by Rebecca Gratz in 1855 and originally located at 799 North 11th Street, the Jewish Foster Home served the Jewish community in Philadelphia and beyond, taking in Jewish orphans from all over the United States. It is unclear when the facility closed. This orphanage moved to Church Lane in 1890. Based on historic maps and information from the files, the home consisted of 7 resources: the main orphanage building (1890), a hospital building (between 1900 and 1924), an unidentified building (probably between 1900 and 1924), a gymnasium (1919), a school and synagogue (1914), and service quarters (1925). Only the synagogue remains today. The rest of the campus appears to have been demolished to make way for expansion of some of the institutions in the area.

Old Age Homes

At the other end of the age spectrum, once people reached the end of their working years, they were often left to their own devices for retirement. As Rauschenbusch states it:

...at present, unless his employer is able and willing to show him charity, or unless by unusual thrift he has managed to save something, he becomes dependent on the faithfulness of his children or the charity of the public. In England, a very large proportion of the aged working people finally 'go on the parish [6].'

The end result was depressing to say the least:

For an old man after a lifetime of honest work to have nothing, to amount to nothing, to be turned off as useless, and to eat the bread of dependence, is a pitiable humiliation [7].

Rauscenbusch saw the solution to these issues in reforming the economic system that led to these outcomes; however, other religious leaders and groups chose to focus their charitable efforts on providing housing for the aged. Based on information in BHP files, it appears that homes for the aged were generally stand-alone facilities (e.g. not part of a larger church complex), either built specifically to house the aged or built as a private residence and adapted to house the aged. Again, for these facilities, function, along with things like number of residents, mission, and so forth, dictated the architectural form. Since numerous religious and secular groups constructed old age homes, the religious association of a facility will most likely be apparent only in its name or in historic documentation.

St. Mary's Home for the Aged

Location:

607 E. 26th Street, Erie City, Erie County, PA

National Register Status:

Undetermined

Description:

Founded in 1894, this old age Home - the facility for a time also took in some orphans to alleviate overcrowding in the orphanage, as well as "the friendless and feeble" - was founded by the Sisters of Saint Joseph and has served Erie's Roman Catholic community up to the present. Originally, the complex consisted of just one building (1884) that was added on to several times (in 1894 with a chapel, in 1906, in 1927 following a devastating fire, in 1929, in 1941); a geriatric hospital was added to the property in 1955. Today, the facility consists of three buildings and the earliest portion of the original building has been demolished.

The Sheltering Arms Home for Aged Protestants

Location:

441 Swissvale Avenue, Wilkinsburg Borough, Allegheny County

National Register Status:

Undetermined

Description:

Opened next to the Home for Aged Protestant Women (1871) in 1872, the Sheltering Arms Home for Aged Protestants began as a home for "wayward" girls (although some aged couples were admitted). By 1881, the mission changed and this property became the Sheltering Arms Home for Aged Protestants [8]. It served the Protestant community of the Pittsburgh area until at least the late 1970s; however, it is not known exactly when (or if) it closed. Originally, the property consisted of one building which was added on to in 1910 (a laundry and two wings). In 1978, more additions were made to the building.

Nugent Home for Baptists

Location:

221 W. Johnson Street, Philadelphia

National Register Status:

Listed (8/30/2006)

Description:

Built in 1895, this property housed the Nugent Home for Baptists, a facility that served aged Baptist ministers, missionaries, and their wives and, when space was available, lay members (in good standing) of the Baptist and other evangelical churches until its closing in 1981. The facility was endowed by industrialist, and deacon in the Baptist Church, George Nugent. The property consists of one building, a grand French Renaissance Revival style building that could house up to 38 people.

Poorhouses/Almshouses

Based on BHP's files, religious organizations seemed to shy away from creating and owning one type of residential institution: the poorhouse or almshouse. For example, of the poorhouses in BHP's files, every one was administered by the county in which it was located. This fact does not mean that religious organizations were not concerned with the welfare of the poor or that they did not support the poor or that religious groups never opened poorhouses. In fact, Quakers created an early poorhouse in Philadelphia in 1713 [9]. It appears, however, that religious organizations felt that residential institutions for the "able-bodied" poor were not an effective solution to the problem (the idea that God helps those who help themselves). Children and the elderly, on the other hand, could not help themselves. Rauschenbusch seems to lend credence to this interpretation:

To accept charity is at first one of the most bitter experiences of the self-respecting workingman. But when they have once learned to depend on gifts, the parasitic habit of mind grows on them, and it becomes hard to wake them back to self-support [10].

Notes

[1] Bateman, Bradley W. "The Social Gospel and the Progressive Era." Divining America, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. Accessed April 11, 2011. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/twenty/tkeyinfo/socgospel.htm.

[2] Page 246.

[3] Page 12.

[4] Folks, Homer. "The Care of Destitute, Neglected, and Delinquent Children." Monographs on American Social Economics. Department of Social Economy for the United States Commission to the Paris Exposition of 1900.

[5] Zmora, Nurith. Orphanages Reconsidered: Child Care Institutions in Progressive Era Baltimore, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994), 198n, 25.

[6] Rauschenbusch, Walter. Christianity and the Social Crisis. New York and London: The MacMillan Company, 1916, 237.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Davison, Elizabeth Mary and Ellen Blanche McKee. Annals of Old Wilkinsburg and Vicinity: the Village, 1788-1888. Wilkinsburg, PA: Group for Historic Research, 1940:459-461.

[9] Pendleton, O.A. "Poor Relief in Philadelphia." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 70(2), (April 1946):161-172.

[10] Rauschenbusch, Walter. Christianity and the Social Crisis. New York and London: The MacMillan Company, 1916, 238.