Developmental History

Definitions

Community - Groups of people living in somewhat close association [1].

Development - A large group of private houses or of apartment houses, often of similar design, constructed as a unified community, especially by a real-estate developer or government organization [2].

Early Automobile Suburbs - communities developed to be condusive to the automobile in design of streets, homes, and such.

Railroad and Horsecar Suburbs - communities that tended to be clustered around passenger stations along railroad lines or along horse-drawn streetcar corridors.

Sprawl - Haphazard growth or extension outward, especially that resulting from real estate development on the outskirts of a city [3].

Subdivision - A portion of land divided into lots for real-estate development [4].

Suburb - A usually residential area or community outlying a city.

Suburbanization - The establishment of residential communities on the outskirts of a city. In the United States, many suburbs were created after World War II, during a period of tremendous growth in population and industry. Suburban dwellers typically work in the cities but raise their families in a less-congested, safer, and more relaxed atmosphere. Especially in the United States, suburbanization often is associated with the sprawl of population [5].

Streetcar Suburbs - clustered around electric-powered streetcar systems, and often formed continuous corridors stretching out from the city core.

Articles and books for further research into developer and builder history and philosophy

Eichler, Ned. The Merchant Builders. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982.

Kelly, Barbara M. Expanding the American Dream: Building and Rebuilding Levittown. New York: State University of New York Press, 1993.

Loeb, Carolyn S. Entrepreneurial Vernacular: Developers' Subdivisions in the 1920s. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Rybczynski, Witold. "How to Build a Suburb." The Wilson Quarterly. Vol. 19 No. 3 (Summer, 1995): 114-126.

Historic Residential Suburbs, an Overview

Most of the components of postwar development existed well before the 1940s, including the trends of subdividers selling lots, providing roads and infrastructure; developers hiring or contracting for design and construction; mass production methods; curvilinear streets and developers acting as large private corporations. It is important to have an understanding of how suburbs evolved in the United States. While the edited narrative presented here briefly discusses suburban land development practices, for the full document, please go to the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register Bulletin Historic Residential Suburbs.

Suburban Land Development Practices

"The basic landscape unit of residential suburban development is the subdivision. The development process starts with a parcel of undeveloped land, often previously used for agricultural purposes, large enough to be subdivided into individual lots for detached, single-family homes and equipped with improvements in the form of streets, drainage, and utilities, such as water, sewer, electricity, gas, and telephone lines. In other suburban neighborhoods, groups of attached dwellings and apartment buildings would be arranged within a large parcel of land and interspersed with common areas used for walkways, gardens, lawns, parking, and playgrounds.

Developers and the Development Process

Until the early twentieth century, most subdivisions were relatively small, and suburban neighborhoods tended to expand in increments as adjoining parcels of land were subdivided and the existing grid of streets extended outward. Subdivisions were generally planned and designed as a single development, requiring developers to file a plat, or general development plan, with the local governmental authority indicating their plans for improving the land with streets and utilities. Homes were often built by different builders and sometimes the owners themselves.

As metropolitan areas established large public water systems and other public utilities, developers could install utilities at a lower expense and often used enhancements, such as paved roads, street lighting, and public water, to attract buyers. Early planned subdivisions typically included utilities in the form of reservoirs, water towers, and drainage systems designed to follow the natural topography and layout of streets. Power plants and maintenance facilities were also included to support many of the larger planned developments of multiple family dwellings.

Historically the subdivision process has evolved in several overlapping stages and can be traced through the roles of several groups of developers.

The Subdivider

Beginning in the nineteenth century, the earliest group of developers, called "subdividers," acquired and surveyed the land, developed a plan, laid out building lots and roads, and improved the overall site. The range of site improvements varied but usually included utilities, graded roads, curbs and sidewalks, storm-water drains, tree planting, and graded common areas and house lots. Lots were then sold either to prospective homeowners who would contract with their own builder, to builders buying several parcels at once to construct homes for resale, or to speculators intending to resell the land when real estate values rose. Land improvement companies typically organized to oversee the subdivision of larger parcels, especially those forming new communities along railroad and streetcar lines. Most subdividers, however, operated on a small scale-laying out, improving, and selling lots on only a few subdivisions a year.(29)

The Home Builder

By the turn of the twentieth century, subdividers discovered they could enhance the marketability of their land by building houses on a small number of lots. At a time of widespread real estate speculation and fraud, home building helped convince prospective buyers that the plan on paper would materialize into a suburban neighborhood. Subdividers still competed in the market through the types of improvements they offered, such as graded and paved roads, sidewalks, curbs, tree plantings, and facilities such as railroad depots or streetcar waiting stations. These developers continued to view their business as selling land, not houses, and the realization of subdivision plans took many years.(30)

The Community Builder

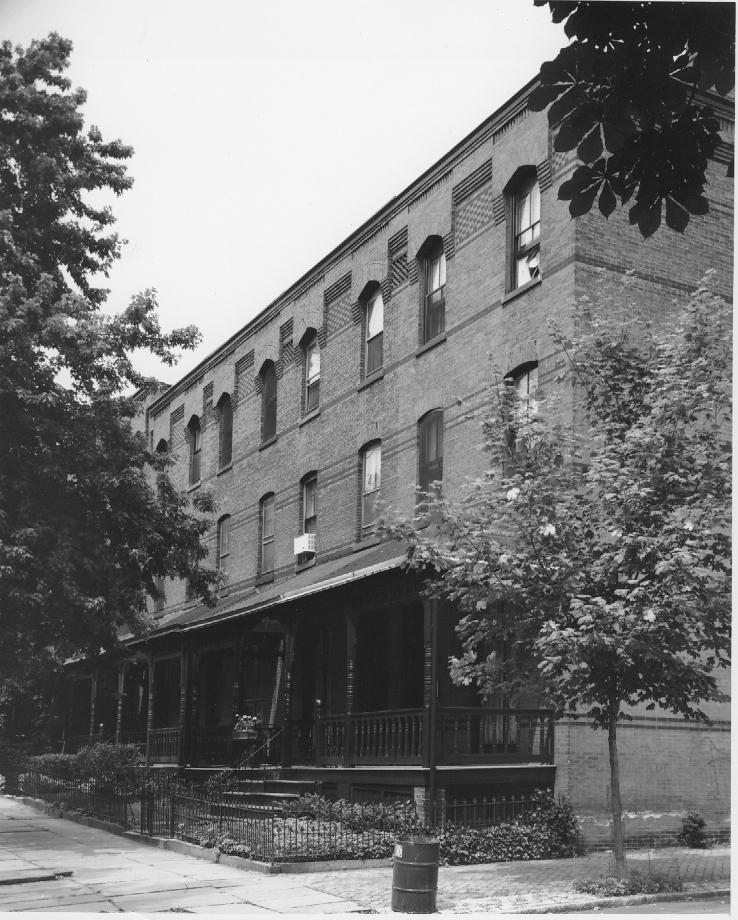

The term "community builder" came into use in the first decade of the twentieth century in connection with the city planning movement and the development of large planned residential neighborhoods. Developers of this type were real estate entrepreneurs who acquired large tracts of land that were to be developed according to a master plan, often with the professional expertise of site planners, landscape architects, architects, and engineers. Proximity to schools, shopping centers, country clubs and other recreational facilities, religious structures, and civic centers, as well as the convenience of commuting, became important considerations for planning new neighborhoods and attracting home owners.(31) Community builders, such as Edward H. Bouton of Baltimore and J. C. Nichols of Kansas City, greatly affected land use policy in the United States, influencing to a large extent the design of the modern residential subdivision. Nichols's reputation was based on the development of the Country Club District in Kansas City-an area that would ultimately house 35,000 residents in 6,000 homes and 160 apartment buildings. Because they operated on a large scale and controlled all aspects of a development, these developers were concerned with long-term planning issues such as transportation and economic development, and extended the realm of suburban development to include well-planned boulevards, civic centers, shopping centers, and parks.(32)

To promote predictability in the land market and protect the value of their real estate investments, community builders became strong advocates of zoning and subdivision regulations. Nichols and other leading members of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) sought alliances with the National Conference on City Planning (NCCP), American Civic Association (ACA), and American City Planning Institute (ACPI) to bring the issues of suburban development within the realm of city planning. (33) Community builders often sought expertise from several design professions, including engineering, landscape architecture, and architecture. As a result, their subdivisions tended to reflect the most up-to-date principles of design; many achieved high artistic quality and conveyed a strong unity of design. By relying on carefully written deed restrictions, as a private form of zoning, they exerted control over the character of their subdivisions, attracted certain kinds of home buyers, and protected real estate values. Many became highly emulated models of suburban life and showcases for period residential design by established local or regional masters. (34)

The Operative Builder

By the 1920s, developers were building more and more homes in the subdivisions they had platted and improved, thereby taking control of the entire operation and phasing construction as money became available. In the 1930s when the home financing industry was restructured, such "operative builders" were able to secure FHA-approved, private financing for the large-scale development of neighborhoods of small single-family houses as well as rental communities offering attached dwellings and apartments. Depression-era economics and the demand for defense-related and veterans' housing which followed encouraged them to apply principles of mass production, standardization, and prefabrication to lower construction costs and increase production time.

The Merchant Builder

Federal incentives for the private construction of housing, for employees in defense production facilities during World War II and for returning veterans immediately following the War, fostered dramatic changes in home building practices. Builders began to apply the principles of mass production, standardization, and pre-fabrication to house construction on a large scale. Builders like Fritz B. Burns and Fred W. Marlow of California began to build communities of an unprecedented size, such as Westchester in southeast Los Angeles, where more than 2,300 homes were built to FHA standards between 1941 and 1944 (35) By greatly increasing the credit available to private builders and liberalizing the terms of FHA-approved home mortgages, the 1948 Amendments to the National Housing Act provided ideal conditions for the emergence of large-scale corporate builders, called "merchant builders." Because of readily available financing, streamlined methods of construction, and an unprecedented demand for housing, these builders acquired large tracts of land, laid out neighborhoods according to FHA principles, and rapidly constructed large numbers of homes. Since completed homes sold quickly, developers could finance new phases of construction and, as neighborhoods neared completion, move on to new locations. On Long Island, William Levitt began building rental houses for veterans in 1947. Soon after he shifted to home sales and perfected the process of on-site mass production which became the basis for the large-scale "Levittowns" he created in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Outside Chicago, Philip Kluztnick, former administrator of the National Housing Agency, with the expertise of town planner Elbert Peets, created the town of Park Forest. In 1949 Fritz B. Burns and Henry J. Kaiser of Kaiser Community Homes built 1,529 single-family homes at Panorama City in California, a suburban community which resulted from the collaboration of Kaiser's industrial engineers and the Los Angeles architectural firm of Wurdeman and Becket. In the late 1940s, Joseph Eichler began the first of his forward looking subdivisions of contemporary homes in California.(36)

Merchant builders greatly influenced the character of the post-World War II metropolis. The idea of selling both a home and a lifestyle was not simply a marketing ploy by developers to ensure sales, it represented the integration of the suburban ideals of home ownership and community in a single real estate transaction. For many, this meant the attainment of middle-class status, financial prosperity, and family stability-the fulfillment of the American dream" [6].

References

[1] community, Dictionary.com Unabridged, Random House, Inc., http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/community (accessed: April 23, 2010).

[2] development, Dictionary.com Unabridged, Random House, Inc., http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/development (accessed April 23, 2010).

[3] sprawl, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/sprawl (accessed April 8, 2010)

[4] subdivision, Dictionary.com Unabridged, Random House, Inc., http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/subdivision (accessed April 23, 2010).

[5] "suburbanization," The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/suburbanization (accessed April 08, 2010).

[6] David Ames L. and Linda Flint McClelland, Historic Residential Suburbs: Guidelines for Evaluation and Documentation for the National Register of Historic Places (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places, September 2002), 26.

|

|

|

|