National Trends

Transportation

It is important to have an understanding of the role and issues of the principal city to its adjacent suburbs. While the narrative included here is from "Urban Transportation Planning in the United States: An Historical Overview," the entire document offers an indepth history of transportation, and coverage of various procedural and legislative highway initatives related to transportation. For further information regarding transportation, see Lee Mertz's "Origins of the Interstate."

"When the war came to an end, the pent-up demand for homes and automobiles ushered in the suburban boom era. Automobile production jumped from a mere 70,000 in 1945 to 2.1 million in 1946, 3.5 million, and 3.5 million in 1947. Highway travel reached its prewar peak by 1946 and began to climb at 6 percent per year that was to continue for decades (Dept. of Transportation, 1979a). The nation's highways were in poor shape to handle this increasing load of traffic. Little had been done during the war to improve the highways and wartime traffic had exacerbated their condition. Moreover, the growth of development in the suburbs occurred where highways did not have the capacity to carry the resulting traffic.

Suburban traffic quickly overwhelmed the existing two-lane formerly rural roads (Dept. of Transportation, 1979a). The postwar era concentrated on dealing with the problems resulting from suburban growth and resulting from the return to a peacetime economy. Many of the planning activities which had to be deferred during the war resumed with renewed vigor.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 was passed in anticipation of the transition to a postwar economy and to prepare for the expected growth in traffic. The act significantly increased the funds authorized for federal-aid highway programs from $137,500 in 1942 and 1943, no funds in 1944 and 1945, to $500,000 annually for 1946 through 1948. The act also recognized the growing complexity of the highway program. The original 7 percent federal-aid highway program was renamed the Federal-aid Primary system, and selection by the States of a Federal-aid Secondary system of farm-to-market and feeder roads was authorized. Federal-aid funding was authorized in three parts, known as the "ABC" program with 45 percent for the Primary system, 30 percent for the Secondary system, and 25 percent for urban extensions of the Primary and Secondary systems.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 launched the largest public works program yet undertaken: construction of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. The act was the culmination of two decades of studies and negotiation. As a result of the Interregional Highways report, Congress had adopted a National System of Interstate Highways not to exceed 40,000 miles in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944. However, money was not authorized for construction of the system. Based on the recommendations of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads and the Department of Defense, a 37,700-mile system was adopted in 1947.

Finally, with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, construction of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways shifted into high gear. The act increased the authorized system extent to 41,000 miles. This system was planned to link 90 percent of the cities with populations of 50,000 or greater and many smaller cities and towns. The act also authorized the expenditure of $24.8 billion in 13 fiscal years from 1957 to 1969 at a 90 percent federal share. The act provided construction standards and maximum sizes and weights of vehicles that could operate on the system. The system was to be completed by 1972 (Kuehn, 1976)." [1]

Dualized highways as "physical features on the American landscape...are pointed to as the products of the nation's obsession with the automobile, are arguably the defining technology of our culture." See Mary McCahon and James Patrick Harshbarger's article "The Importance of Using Context to Determine the Significance of Dualized Highways." (PDF)

Further Keyword Research Suggestions:

- American Association of State Highway Officials

- Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, 1956

- A Policy on Geometric Design of Rural Highways (1954) - the "Blue Book"

- U.S. Bureau of Public Roads

- U.S. Department of Transportation

- U.S. Federal Highway Administration

- Highway Research Board

- Highway Planning Program Manual

- Eisenhower Interstate System

- U.S. Public Roads Administration

- Highway Users Conference (1952)

- "Project Adequate Road" (1952)

- "A Ten-Year National Highway Program" (1955)

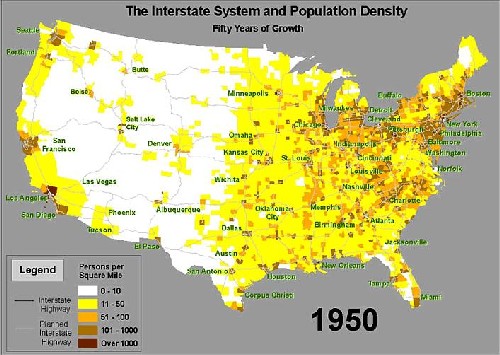

Map of the United States Interstate System and Population Density in 1950. Courtesy of Federal Highways Administration. |

Housing Legislation

Through sixteen years of depression and war, the residential construction industry of the United States had been all but dormant, with less than 100,000 new homes being constructed nationwide a year. During the war years, many people in search of housing (and often jobs as well) had migrated to defense areas, but this temporary housing was not designated to be converted to permanent housing at the wars end. As veterans returned home, marriage and birth rates skyrocketed reaching twenty-two per thousand in 1943. This combined with the shortage of housing during the war period meant that there were virtually no homes for sale or apartments to rent to returning veterans and their families. Many families were doubling up as they had done in the depression years, but this did not fix the problem. Large cities such as Chicago, Omaha, and Atlanta converted trolley cars, iceboxes, and trailers into homes for veterans to attempt to alleviate the housing shortage. However, by 1945, there were 3.6 million families lacking a permanent home or apartment.

Yet, the government and housing industry had seen the problem coming many years before. During the war period, the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) created the Home Builderss Emergency Committee, which started to focus on the great housing shortages that would accumulate with the war veterans return home. Independent groups such as the American Builder magazine researched and published plans for veteran housing in the postwar. The American Builder stated they planned to build a million postwar homes a year with Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Title VI loans of 25-30 years and 5% down. The NAHB embraced this plan and created their own program of 5%, and 25-year FHA loans at 4.5% interest. Congress soon joined the FHA and in 1943 began to debate postwar legislation as well as authorized a $400 million extension to the FHA home financing.

Further Keyword Research Suggestions:

- Reconstruction Finance Corporation

- National Housing Act of 1934

- Federal Works Agency

- National Housing Agency

- Federal Housing Administration

- Veterans Administration

- Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944

- Taft Ellender Wagner Act (1945)

- Housing Act of 1949

- Housing Act of 1954

- National Association of Home Builders

- Home Builders' Emergency Committee

- Urban Land Institute

- National Association of Real Estate Boards

- Community Builder's Handbook

- American Builder

FHA Documents

- Minimum Property Requirements (1942)

- Minimum Requirements for Rental Housing Projects (1942)

- Master Draft of Proposed Minimum Property Requirements for Properites of One or Two Living Units (1945)

- Significant Variations of the Minimum Property Requirements of FHA Insuring Offices (1947)

- Minimum Property Standards for One and Two Living Units (1958)

Subdivision Design

The following narrative continues the discussion of subdivision development across the United States into the postwar period, and is taken from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register bulletin Historic Residential Suburbs.

Trends in Subdivision Design

"To Seward Mott, who headed FHA's Land Planning Division, the legislation's mandate provided an opportunity to redirect the design of suburban America and to create conditions that would force public officials and planners alike to adopt planning measures and to abandon the rectilinear grid in favor of plans of curvilinear streets. Curvilinear plans had many advantages when compared to rectilinear gridiron plans: they provided greater privacy and visual interest; could be adapted to greater variations in topography; reduced the cost of utilities and road construction; and, by eliminating the need for dangerous four-way intersections, provided a safer environment for domestic activities.(93) The curvilinear layouts recommended by FHA in the 1930s set the standards for the design of post-World War II subdivisions. They evolved from Garden City suburbs such as Seaside Village and Radburn, and the organic curvilinear designs of the nineteenth-century Picturesque suburbs. Highly influential were Olmsted and Vaux's Riverside, with its spacious plan of undulating and recessed, curvilinear streets, and Roland Park with its careful subdivision of land based on topography and the development of curvilinear streets that joined at oblique and acute angles and ended in cul-de-sacs in hollows or on hillside knolls. By the 1930s, such principles of design had been absorbed into the mainstream practices of the landscape architectural profession.

The Postwar Curvilinear Subdivision

Through FHA's publication of standards for neighborhood planning and its comprehensive review and revision of subdivisions for mortgage approval, curvilinear subdivision design became the standard of both sound real estate practice and local planning. As FHA-backed mortgages supported more and more new residential development on the edge of American cities, local planning commissions adopted some form of the FHA standards as subdivision regulations. Thus, by the late 1940s, the curvilinear subdivision had evolved from the Olmsted, City Beautiful, and Garden City models to the FHA-approved standard, which had become the legally required form of new residential development in many localities in the United States. Based on the Garden City idea, the greenbelt communities built by the U.S. government under the Resettlement Administration during the New Deal became models of suburban planning, incorporating not only the Radburn Idea but also the FHA standards for neighborhood design.(97)

The curvilinear subdivision layout was further institutionalized as the building industry came to support national regulations that would standardize local building practices and reduce unexpected development costs. One of the most influential private organizations representing the building industry was the Urban Land Institute (ULI), established in 1936 as an independent nonprofit research organization dedicated to urban planning and land development. Sponsored by the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) and serving as a consultant to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), ULI provided information to developers about community developments that supported land-use planning and promoted the idea of metropolitan-wide coordination as an approach to development.(98)

In 1947 the ULI published its first edition of the Community Builder's Handbook. Providing detailed instructions for community development based on the curvilinear subdivision and neighborhood unit approach, it became a basic reference for the community development industry and, by 1990, was in its seventh edition. In 1950 the NAHB, the primary trade organization for the industry, published the Home Builders' Manual for Land Development. Thus, by the late 1940s, the concept of neighborhood planning had become institutionalized in American planning practice. This form of development, in seamless repetition, would create the post-World War II suburban landscape." [2]

Notes

[1] Edward Weiner, Office of Economics, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy and International Affairs, Office of the Secretary of Transportation, "Urban Transportation Planning in the United States: An Historical Overview," Revised Edition November 1992, available at http://ntl.bts.gov/DOCS/UTP.html

[2] David Ames L. and Linda Flint McClelland, Historic Residential Suburbs: Guidelines for Evaluation and Documentation for the National Register of Historic Places (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places, September 2002), 49.