Chambersburg War Damage Photos and Claims - 1864, 1866

Images

Click images for larger versions.

History

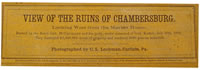

Record Group 2: Records of the Auditor General, Chambersburg War Damage Claim Applications (Submitted under Act of Feb. l5, l866),"Claim of B. L. Schneck, March 19, 1866" and Manuscript Group 218: Photograph Collections, Panoramic photograph, "View of the Ruins of Chambersburg Looking West from the Market House," albumin print 36 1/2" X 15 1/2" by Charles L. Lochman of Carlisle, PA.

On July 30, 1864, Confederate troops entered the south central Pennsylvania town of Chambersburg. Their commander General John McCausland demanded from the residents $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in cash. When the residents refused to pay, he ordered his troops to burn the town.

This was not the first visit by the Confederates to Chambersburg. In October, l862, Major General J.E.B. Stuart led 1,800 troops into the area. They inflicted little damage and, except for a large number of horses that they "liberated," paid for most of what they took, albeit in devalued Confederate money. In the early summer of the following year as General Robert E. Lee led his 50,000 strong Army of Northern Virginia toward Gettysburg, several units occupied Chambersburg. Although they obtained supplies they did no large-scale plundering or destroying of property.

The attack by McCausland's forces was different. They attacked more severely, robbing residents on the streets, plundering their homes, and setting fire to private as well as public buildings. Occupants were ordered to vacate at once. Those who were physically unable to leave were left to burn, though all but one were rescued by heroic neighbors. Residents who tried to take possessions with them as they left their homes often had them stolen by the troops afterward. Several homeowners paid Confederates to spare their property; after receiving the bribes, the troops still set fire to their homes. Not all Confederates participated in wanton destruction willingly. Even General McCausland complained that his assignment did not appeal to some. One officer helped residents take clothes and other belongings from their homes before burning them. A Confederate cavalry unit prevented other troops from setting fires in much of southeastern Chambersburg.

Nevertheless, as a close examination of the panoramic photograph by Charles Lochman, illustrates the extensive damage to the town. The caption claims that the Confederates "destroyed" $3,000,000 worth of property and rendered 3,000 persons homeless. At least ten square blocks in downtown Chambersburg lay in ruins. Public buildings, including the Franklin County Courthouse, Bank of Chambersburg, the printery of the German Reformed Church, numerous stores as well as many private homes perished in the flames.

In 1866, Pennsylvania's Legislature passed an "act for the relief of certain citizens of Chambersburg and vicinity whose property was destroyed by the rebels on the thirtieth of July 1864." Victims of the attack were to be free of "countenances and encouragement to the traitors" (Confederates) and were required to list specifically what they lost with its monetary value. Because many residents lost all of their possessions, their applications for reimbursement reveal much about how they lived.

Many of their homes were of moderate size, built of brick or wood. Some were carpeted and furnished with tables chairs, cupboards, wardrobes, washstands, bedsteads, and lamps. Most kitchens were well stocked with eating utensils, kettles, and food supplies such as flour, lard, vinegar, and hams. Grocers provided sugar, syrup, coffee, chocolate, spices, soda, and other edibles. Clothing in the inventories included dresses, bonnets, aprons, trousers, suspenders, shoes, stockings, shirts, and undergarments. Indicative of the climate were shawls and coats.

Benjamin Schneck's claim included the normal personal and household items but also some that were peculiar to his profession as clergyman and editor of the German Reformed Church's magazine. He noted as burned his entire Library of theological, historical and "Miscellaneous books, including Maps, Charts, many Volumes of Reviews, etc.- over 1200 volumes". Undoubtedly, this was an irreplaceable loss. His inventory is more precisely detailed than others and contains more valuable items, such as "1 Rosewood 7 Octave Piano, a Mahogany Sideboard," "fine China," "A silver fruit basket," and "5 Chamber sets for 5 rooms." The comparatively high value that he placed on these items suggests his upper middle class social standing.

Why the Confederates chose Chambersburg is not clear. Ransom was demanded and payment made by other nearby towns of Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland and York, Pennsylvania. Chambersburg's refusal to do so might have left them vulnerable. McCausland gave as his sole reason Chambersburg's accessibility, located just north of Virginia. Most of the Union forces who had protected southern Pennsylvania had been withdrawn to protect the national capital at Washington. General Darius Couch, the commander of the few remaining troops in the area was incompetent and failed to respond previously to Chambersburg residents pleas for help. Perhaps the Confederates knew that John Brown had stored weapons in Chambersburg and that he had proceeded from there to attack the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry in order to incite the slaves to rebel. Most immediate may have been the Confederates' desire for revenge for Union General David Hunter's burning of numerous buildings in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, including even the home of the uncle who had raised him. If the Confederates had been able, they might have exacted even greater revenge after Union General Philip Sheridan's devastating raids in the Shenandoah Valley in the fall of 1864, a few months after McCausland's forces burned Chambersburg and General William T. Sherman's "March through Georgia." Both of these expeditions produced massive destruction along their routes. Fortunately, the Civil War ended in mid-April 1865, and people on both sides attempted to "bind up the nation's wounds."

Transcript

(spelling and usage retained from original document)

No. 120, Claim of R.J. Schneck, Losses Claimed: Real Estate - $3,000

Personal Property - 3,728.50

Total - $6,728.50

[reduced?] – 200.00

Filed – 6,428.50

Three thousand seven hundred and twenty eight and 5-/100 Dollars, making a total award of six thousand seven hundred and twenty eight and 50/100 Dollars

Jno. M. Gilman, Clerk

(Illegible), Appraisers

STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA, Franklin County, SS.

Before me, a Justice of the Peace, in and for the said County, personally appeared R.J. Schneck, who being duly Affirmed did depose and say, that the within statement of losses sustained by deponent , by burning of Chambersburg by the Rebels, on the 30th of July, A.D. 1864, is just and true; that all the property therein described was owned by the deponent and was destroyed by the fire by the Rebels on said day, and that the valuation is no more than the actual cash value of the property at the time it was destroyed; and further, that the deponent never did , directly or indirectly, by word or act, give aid, comfort, or countenance to the Traitors , whether in arms or otherwise, and that the deponent has never communicated, or attempted to take means to communicate to them, or any of them, any information which could in any way be of advantage to them.

R.J. Schneck

Affirmed and subscribed before me this 19th day of March, 1866, B.R. M------(?), J.P.

Toward: $428 50/100

18 August 1871 Claim Approved for the ----- four hundred and twenty eight 50/100 dollars

J.M. (Duffy?), Jacob Pensinger, Commissioners

Claim of Rev? 73 S. Schneck, D.D. presented for adjudication before Appraisers of an Act entitled “An Act for the relief of certain citizens of Chambersburg and vicinity, whose property was destroyed by fire, by the Rebels, on the 30th day of July, 1864.” ApprovedFebruary 15th, 1866.

1 Five Stories Stone & Brick building on East Market Street. - $3,000.00

1 Rosewood 7 Octavo Piano (nearly new) $350, Piano Stool $10 – 360.00

My entire Library of Theological, Historical & Miscellaneous books, including Maps, Charts, many volumes of Reviews, Ye 0ver 1200 Volumes – 1,500.00

(I may specify a few as follows:

6 large Vols. Of History of Languages & Lexicography by Grim (German, new) $40

4 large Vols. Olshausen’s Commentary (new) $20 – Vols. Gerlach’s ditto per - $30

6 large Vols. Lange’s Exeget. Homilies & Critical ditto $15. Henry’s ditto &8. – 23.00

2 large Vols. Clarks do. $15 – Greek & Latin Dictionary $8 Gk. Testament $4 – 12.00

12 large Vols. Conversations Lexicon (German) $25, Kott’s Bible Dictionary 5 – 30.00

1 large Vol. Calmet’s Dict. Of Bible $7, Horne’s Intro. To Bible (2 Vols) $6 – 13.00

15 large Quarto Vols. Hengstenburg, Keelog Gazetteer, bound $2 – 11.50

2 large Volumes Hengstenbergs Christology $6. 1 Vol. Longs Com. (English) by Dichoff $5 – 11.00

10 large Vols. Biblioteck chira $25 – 20 Vols. Ger. Ref. Messenger (bound) $40 – 65.00

12 large Vols. Princeton Review (bound) $30 – 20 Vols. Merceesb(? ) Review (bound) 40 – 65.00

Dr. Netzsch’s, Dr. Ebrard’s, Dwight’s & Chalmer’s Theology – 45.00

Chevalier Bunsen’s Historical Theol. Works Ye Ye – 10.00

(Large boxes full of Pamphlets, Magazines etc. (some especially valuable) not brot into account)

In the Parlor: 40 yards Brussels Carpet (little wear) @ $1.12 per yard – 45.00

4 Venetian Blinds $20, One Mahogany Sofa $20 ½ doz. Chairs at 4 $24 – 64.00

1 Fancy Chair $5, Two Large Mahogany Chairs $4, Two small fancy tables $8 – 17.00

2 Reception Chairs $5, What-Not $10 – 15.00

17 framed Pictures & various Books of Engravings (some large) collected in Europe – 50.00

Parlor Ornaments (Italian Alabaster of various Kinds & sizes – 25.00

1 Looking Glass $10, One Bracket $3 – 13.00