Revolutionary War Forfeited Estates - 1779

Images

Click images for larger versions.

History

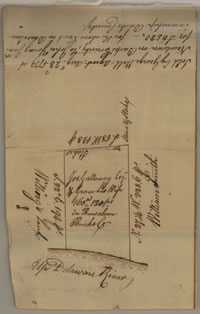

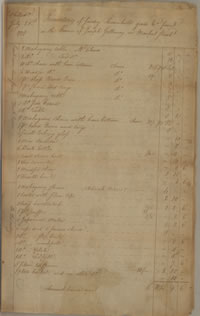

Record Group 27: Records of Pennsylvania's Revolutionary Governments, Supreme Executive Council, Forfeited Estate Files. Two items from file on Joseph Galloway, 1779: 1. a list of possessions and 2. a survey map of his home along the Delaware River.

After the French and Indian War, British officials concluded validly that some American colonists had not acted with the Empire's best interests in mind. The royal governor of South Carolina and Virginia militia commander George Washington charged that Americans deserted frontier garrisons that had been established for their own protection. Indeed, Pennsylvania's legislature had not even authorized a militia until 1756, two years after hostilities had begun in its interior. Furthermore, during the war, colonial merchants in the seacoast cities shipped food products to the non-British West Indies, knowing that eventually they would feed the French troops who were moving into the back country of what government officials considered British America. Such trade was illegal in times of peace and treasonous during the War with France (1756-1763). Nor did the colonists bear their share of the cost of the war that Britishers claimed they fought for the colonists' protection.

Consequently, British officials revised their policy toward the American colonists. They tightened enforcement of trade laws, for squatters settling in Indian lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, stationed troops in the colonies, and attempted to tax the colonists. These measures were reasonable from the British point of view.

Many colonists considered the British actions obnoxious and resisted. Although Bostonians may have led the protests, Philadelphians were not far behind. In 1767, one of its attorneys, John Dickinson, wrote a classic argument against taxation by the British Parliaments charging that it was an unconstitutional denial of the colonists' "natural rights." Its merchants threatened not to import British goods. Artisans formed committees that corresponded with others elsewhere. There were rallies in the streets, one of which forced a British tea ship to return to England--still loaded with tea that the colonists refused to drink. After Paul Revere rode to Philadelphia to inform Pennsylvanians that Parliament passed a series of acts that closed the port of Boston, and Massachusetts's legislature, residents of Pennsylvania's hinterland began to express their concern.

Despite the volume of opposition to British actions during the 1760s and early 1770s, not all Pennsylvanians were willing to support revolution. Pacifistic members of the Society of Friends (Quakers) and German sectarians opposed the War for American Independence on religious grounds. Some wealthy merchants and land-owners feared the loss of their social and economic status if their connection to British aristocrats were severed. A few others advocated postponing military action in the hope that further negotiations could resolve the divisive issues.

One of the best-known opponents of American independence was Joseph Galloway. Born in Maryland in 1731 to Quaker parents who moved to Delaware, in 1740, in his late teens, he came to Philadelphia, where his family had business interests. He studied law, married into the upper class Growden Family, and rose rapidly socially, professionally, and politically. He was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1756 and became its Speaker a decade later, a position which he held until 1774 when he was elected to the First Continental Congress. For that body he prepared a "Plan of Union" of Great Britain's American colonies that included a President general to be appointed by the Crown and an inter-colonial "Grand Council" to be elected by the colonies' legislatures. It was intended to reconcile the colonists to the "Mother Country." When the Congress rejected his proposal, he withdrew. After the Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence in early July, 1776, he went to New York and joined the British Army. There he became an advisor to General William Howe, telling him inaccurately that 90% of Americans would support his vigorous suppression of the Revolution. While the British forces occupied Philadelphia from September 1777 until June 1778, Galloway served them as "Superintendent General of Police" and "Superintendent of the Port" which gave him a vast array of powers that he used against the rebels. When General Howe resigned and the new British commander General Henry Clinton moved the army from Philadelphia to New York, Galloway feared for his safety and went with the army, taking along his daughter but leaving his wife to protect his property. In October 1778, he went to England where he continued to urge the British to put down the rebellion.

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania Assembly, meeting in Lancaster, passed an "act of attainder" on March 6, 1778, that required alleged Loyalists to face trial or risk forfeiture of their estates. The Assembly hoped to pay the cost of government with funds produced by the sale of Loyalists' property. As one of the wealthiest men in the Commonwealth, and an accused collaborator, Galloway's property was seized and sold at auction. The documents, including the map, show the location of some of his lands along the Delaware River and some of his possessions, including furniture, bedding, curtains, kitchen utensils and tools. It should be noted that this was not Galloway's only estate to be taken and that Galloway was not the only Loyalist to have his property confiscated. From England, Galloway attempted to persuade the Pennsylvania Assembly to return his property but in vain. He was not consigned to poverty, however. In 1783, the British government granted him a sizeable annual pension of £500. In time, some of the lands that had come to Galloway through his marriage to Grace Growden were restored to their daughter Betsey.

Transcript

(spelling and usage retained from original document)

Forfeited Estate of Jos. Galloway Esq. and Grace his Wife – 160 acres and 120 perches in Bensalem, Bucks Co. [located along the Delaware River]. Sold by George Wall, Agent, Aug. 23, 1779 at Newtown in Bucks County, to John Young Jun. for 6,580 pounds – for the above Tract in Bensalem Township, Bucks County.

Philadelphia, July 21, 1778

Inventory of sundry Household goods found in the house of Joseph Galloway in Market Street.

Front room downstairs

2 Mahogany tables w. chairs – 15

2 Ditto, chairs ditto – 12

10 ditto chairs with hair bottoms – 10

1 Pr. Brass Hand Irons – 6

1 pr. Shovel and Tongs – 2

Back Room

1 Mahogany table – 5

1 [Mahogany] Side Board – 8

1 [Mahogany] Table – 3.10

8 Mahogany Chairs with hair bottoms – 32

1Pr. Hand Irons and tongs – 3

1 Small looking glass – 0.10

1 Wine Decanter – 0.5

6 Glass Bottles – 0.5

1 Small China Bowl – 0.13

1 Tea Cannister – 0.2.6

1 Windsor Chair – 1.10

1 Hearth [illegible] – 0.2.6

On the Entry

1 Mahogany Skreen (Deborah Morris)

1 Caster with Silver Top

9 Brass Candlesticks

1 Pair of Snuffers

3 Japanned Waiters – 1.2.6

6 Cups and Saucers China – 3.0.0

1 ditto Slop Bowl – 2.6

1 ditto Cream Pot – 3.0

1 ditto Yelato – 5.0

1 ditto Tea Pot – 7.6

8 Silver Tea Spoons – 2.10

1 Plate Basket and other ditto – 10.0

Amount Carried Over – 15.9.6