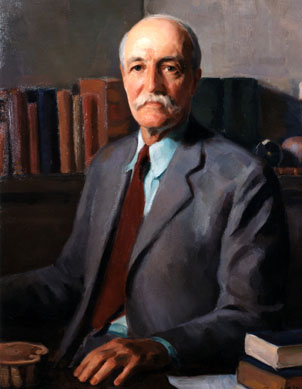

Governor Gifford Pinchot

Terms

January 16, 1923 - January 18, 1927

January 20, 1931 - January 15, 1935

Affiliation

Republican

Born

August 11, 1865

Died

October 4, 1946

Photo courtesy of Capitol Preservation

Committee and John Rudy Photography

Biography

If Gifford Pinchot had not become governor of Pennsylvania, he would be still famous for his legacy reagarding America's forests. In fact, Pinchot was quoted as saying, "I have been governor every now and then, but I am a forester all the time." Pinchot was born August 11, 1865, to Episcopalian parents in Simsbury, Connecticut, the son of James W. Pinchot, a successful New York City wallpaper merchant and Mary Eno, daughter of one of New York City's wealthiest real estate developers, Amos Eno. The first member of Pinchot's family in Pennsylvania, Francis Joseph Smith, came from Belgium with a letter from Benjamin Franklin to Robert Morris, and after serving as major in the Revolutionary War, settled in the Delaware Valley at Shawnee, now in Monroe County. Pinchot's great grandfather, Constantine Pinchot, and his grandfather, C.C.D. Pinchot, settled in Milford, Pike County, in 1816. James Pinchot was born in Milford and built the present Pinchot mansion there in 1886. The former governor's home, known as Grey Towers, is now owned by the USDA Forest Service (founded by Pinchot) and is a national historic landmark.

Governor Pinchot received his preparatory education at Philips Exeter Academy, Exeter, New Hampshire, and was graduated from Yale University in 1889. Pinchot was determined to establish forestry as a legitimate occupation, despite the fact that forestry was not a recognized profession at that time in the United States. Amos Eno offered his grandson a business position that most likely would have made Pinchot independently wealthy, but Pinchot considered forest conservation a more important calling. With his father's encouragement, he studied forestry in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Austria. In January 1892, Pinchot, at the invitation of George Vanderbilt, created the first example in the United States of practical forest management on a large scale at Vanderbilt's Biltmore Estate, near Ashville, North Carolina. Proving that conservation practices could be both beneficial for forests and still profitable, the Biltmore arboretum became a model for forest management around the world.

From 1898 to 1910, Pinchot consolidated the fragmented government forest work under the U. S. Division of Forestry, later the Bureau of Forestry, and then the United States Forest Service. In 1903, Pinchot also became professor of Forestry at Yale University and, in 1904, his friend President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him chief of Forestry. Under Pinchot's guidance, the number of national forests increased from 32 in 1898 to 149 in 1910. Pinchot and Roosevelt agreed on many points of conservation and worked tirelessly to end the destruction of U.S. forests.

Pinchot also visited the Philippine Islands in 1902 and recommended a forest policy for the islands. He was appointed by President Roosevelt to the Committee on Organization of Government Scientific Work in 1903; to the Commission on Department Methods in 1905; to the Inland Waterways Commission in 1907; and, in 1908, to the Commission on Country Life, Chairman of the National Conservation Commission, and Chairman of the National Conservation Commission. He was also appointed chairman of the Joint Committee on Conservation, by the first conference of Governors at Washington, December 1908. In 1917, he was a member of the U.S. Food Administration.

On August 15, 1914, Pinchot married Cornelia Elizabeth Bryce (1881-1960), a native of Rhode Island and daughter of a wealthy journalist and politician, Lloyd Bryce. Cornelia and Gifford both were longtime friends with Theodore Roosevelt, who attended their wedding. As one of the most politically active first ladies in the history of Pennsylvania, she was a very strong advocate for women's rights, full educational opportunities for women, seeking wage and union protections for women and children, and encouraging women to participate in the political process. Her family's wealth, influence from socially and politically prominent relatives, and Progressive Era politics proved to be a great influence on her husband's political agenda. Her influence among female voters is credited as a key factor in the election of her husband. Cornelia Bryce Pinchot ran for the U.S. House of Representatives three times and attempted to succeed her husband as governor in the primary of 1934, but lost all four elections. It was not until 1942 when Pennsylvania elected the first woman to Congress, Veronica Grace Boland (1899-1982) and only five other women between 1942 and 2009—Vera Daerr Buchanan (1951), Kathryn Elizabeth Granahan (1955), Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky (1993), Melissa Hart (2001), and Allyson Y. Schwartz (2005, still serving as of 2009).

Pinchot also created forest ranger jobs for Native Americans, as well as a plan of compensation for tribes cheated by unscrupulous lumbering contracts. However, politics and special interests brought Pinchot's role in the Division of Forestry to an end. He often found himself at odds with Richard Achilles Ballinger (1858-1922), who replaced James R. Garfield (1865-1950) as commissioner of the General Land Office and as secretary of the interior, 1909-1911, under President William Taft. Ballinger opposed many conservation policies and regarded some actions by Pinchot and Roosevelt as illegal. As long as Roosevelt was in office, Pinchot was able to accomplish many conservation goals. Even though Pinchot had the support of the majority of Congress and Taft promised publicly to continue Roosevelt's conservation policies, and despite Pinchot's resistance to more extreme conservationists, Taft came down on the side of industry and removed Pinchot from office. Reclaiming lands and forests for federal protection meant taking away profits from corporations interested in mining, logging, and water resources.

Pinchot first expressed interest in running for governor in 1910, but he did not then meet Pennsylvania's minimum length of residency, which was seven years. In 1914, he ran for U.S. Senator, but lost to political boss Boies Penrose. When Penrose died in 1921 and Governor William C. Sproul divided Republican Party liberals and conservatives, it created an opportunity for the independent-minded Pinchot, who was serving as commissioner of Forestry of Pennsylvania between March 10, 1920, and April 13, 1922. Sproul supported George E. Alter of Allegheny County, so Pinchot ran as an underdog. While Alter won in Philadelphia and Allegheny Counties, Pinchot carried sixty-one of sixty-seven state counties and won by just 9,259 votes in the primary. Significant in voting that year was this was the first gubernatorial election in which women could vote. With Pinchot's support of women's issues, his strong support of Prohibition and other moral issues, his reputation as a conservationist, and the influence of his wife Cornelia, Pinchot easily defeated his Democratic opponent, John A. McSparran, 831,696 to 581,625 votes.

During his first term in office, the governor was known for his accessibility to the public and Pinchot concentrated on the regulation of electric power companies and reorganizing state government. A $23 million state deficit was eliminated under his administration and he revised laws for care and treatment of the mentally ill and retarded, devised a state employee retirement system, an old age pension system, and settled a coal mining strike in 1923. He favored a revision of the state constitution, but, unable to gain enough support, he settled for a new 178-page administrative code.

Prohibited by the state constitution from succeeding himself, Pinchot again ran for the U.S. Senate in 1926, but ran third behind William S. Vare and George Wharton Pepper. It was Governor Pinchot's duty to issue a certificate of election to Vare, but wrote that the election was, "partly bought and partly stolen." After a U. S. Senate investigation, Vare was denied a seat because of fraud and corruption. Vare, from a powerful Philadelphia political dynasty, became one of Pinchot's enemies and put his forces behind Francis Shunk Brown, grandson of former Governor Shunk. Joe Grundy, an influential Bucks County millionaire and foe of Vare, was key to garnering support for Pinchot. Credit was also given to future Governor John S. Fine who helped make sure ballots were handled fairly in Luzerne County where there was a reputation for fraudulent elections. Pinchot defeated Brown in the primary by 20,000 votes, having won Luzerne County by more than 26,000 votes, and despite Brown's win in Philadelphia by 190,000 votes. In the 1930 November election, Republican anti-Pinchot political forces, led by Vare, and those who favored repealing Prohibition, opposed Pinchot, but Pinchot still managed to defeat Democrat John M. Hemphill by more than 32,000 votes out of two million cast.

During Pinchot's second term, Pennsylvanians were suffering from the Great Depression. State unemployment rose from 11.8 percent when he took office to 40.2 percent when he left office. It was within this economic backdrop that Pinchot worked to reach other goals, including: a reduction in utility rates, pensions for the blind, and, following federal law, curbing abuses by corporations and financial  institutions. He also saw to improvements in 20,000 miles of rural roads; the creation of the Sanitary Water Board, the first anti-pollution agency in the country; and the purchase of the Indiantown Gap Military Reservation. Also updated was the juvenile court system and repeal of the requirement that voters present tax receipts as a quasi poll tax. Other Pinchot proposals to help citizens during the Depression were often met with resistance from a conservative "do nothing" legislature. For example, a Pinchot proposal to provide unemployment compensation was not passed, although it finally became law with the next governor.

institutions. He also saw to improvements in 20,000 miles of rural roads; the creation of the Sanitary Water Board, the first anti-pollution agency in the country; and the purchase of the Indiantown Gap Military Reservation. Also updated was the juvenile court system and repeal of the requirement that voters present tax receipts as a quasi poll tax. Other Pinchot proposals to help citizens during the Depression were often met with resistance from a conservative "do nothing" legislature. For example, a Pinchot proposal to provide unemployment compensation was not passed, although it finally became law with the next governor.

Pinchot, at six-foot, one-inch tall, was always athletic. He was captain of the Yale freshman football team, once played Teddy Roosevelt six straight sets of tennis and then raced the president to the White House. While governor and in his 60s, he was a student pilot and won a 75-yard dash against a much younger cabinet member. His energy, maverick philosophy, and a magnetic and dynamic personality were part of his public appeal. In 1938, the Depression had contributed to ending the hold of Republicans in Pennsylvania's government. At first, the only candidate thought to have a chance of restoring a Republican governor was Pinchot, then age seventy-three. However, support swung to Arthur H. James, who was elected, thus bringing an end to Pinchot's political career.

Pinchot continued his work on behalf of conservation and, therefore, adding to his legacy. Over his lifetime he was a member of the National Farmers' Union, the Pennsylvania State Grange, the executive committees of the National Board of the Farm Organizations and the Pennsylvania Y.M.C.A. He was a member of the University and City Clubs of Philadelphia. He authored several books, including: The White Pine (with H. S. Graves), 1896; The Adirondack Spruce, 1898; A Primer of Forestry, Part 1, 1899, Part 2, 1905; The Fight for Conservation, 1910; The Country Church (with C.O. Gill), 1913; The Training of a Forester, 1914; Six Thousand Country Churches (with C.O. Gill), 1919; To the South Seas, 1930; and, his autobiographical record of his conservation years, Breaking New Ground, 1947.

Pinchot had one child, Gifford Bryce Pinchot. Gifford Pinchot died on October 4, 1946, and is buried in Milford Cemetery, Pike County. Not only is Gifford Pinchot State Park in northern York County named after him, but a year after his death, Cornelia Pinchot spoke at the dedication of Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington State.

Pages in this Section

- 1876-1951

- John Frederick Hartranft

- Henry Martyn Hoyt

- Robert Emory Pattison

- James Addams Beaver

- Daniel Hartman Hastings

- William Alexis Stone

- Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker

- Edwin Sydney Stuart

- John Kinley Tener

- Martin Grove Brumbaugh

- William Cameron Sproul

- Gifford Pinchot

- John Stuchell Fisher

- George Howard Earle

- Arthur Horace James

- Edward Martin

- John Cromwell Bell Jr.

- James Henderson Duff