Governor John Stuchell Fisher

Term

January 18, 1927 - January 20, 1931

Affiliation

Republican

Born

May 25, 1867

Died

June 25, 1940

Photo courtesy of Capitol Preservation

Committee and John Rudy Photography

Biography

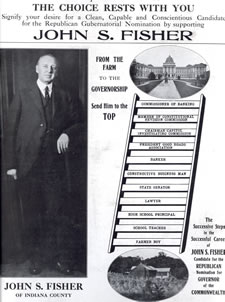

John Stuchell Fisher followed a familiar path for Pennsylvania governors—a farm boy who began his career as a teacher. Fisher was born May 25, 1867, two miles north of Plumville in South Mahoning Township, Indiana County. He was one of six children of Samuel Royer and Mariah (McGaughey) Fisher, and descended from families identified with Pennsylvania as early as 1726 when his fourth great-grandfather, Jacob Fischer, emigrated from the Palatinate.

Governor Fisher was educated in Indiana, Pennsylvania, public schools and graduated from Indiana High School in 1884, followed by Indiana Normal School (later renamed Indiana State College and now known as Indiana University of Pennsylvania) in 1886. At age nineteen, he began teaching at Ox Hill School where he had begun his education. By the time he became governor, Fisher was vice president of the board of trustees at Indiana Normal School. In 1888, while teaching at a two-room school in Plumville, he met teacher Hapsie Miller. They were married on October 11, 1893, and were parents of four children, two who died in infancy. Hapsie Fisher did not live to see her husband become governor as he was widowed in 1922.

During the seven years he taught, he also became principal of Indiana public schools in 1891 and, when he was not teaching, studied law with former congressman and attorney Alexander W. Taylor who had a great influence on Fisher. Just out of high school, Fisher had campaigned at age seventeen on behalf of a Taylor friend and Taylor recognized a highly intelligent young man. In August 1893, just three months after his law mentor died, Fisher was admitted to the Bar of Indiana County, practicing with his own firm, Cunningham and Fisher. The firm became one of the largest and most successful in Indiana County. With this additional prestige, Fisher became chairman of the Indiana County Republicans in 1896. His first taste of running his own campaign occurred at age twenty-one when he made an unsuccessful bid to become superintendent of county schools. However, in 1899, he easily won election to the state senate, serving from 1900 to 1908 and re-elected once. Fisher's Jefferson and Indiana Counties shared a political custom of limiting their local senators to just two terms, which the senator honored, but in his last term as senator, Fisher gained statewide recognition.

When State Treasurer William H. Berry uncovered the misappropriation of state funds in furnishing the new state Capitol Building in 1906, Fisher was appointed chairman of the investigative committee, which was generally lauded by the press. Striving for an impartial finding and after forty-eight hearings, 289 exhibits, 189 witnesses, and four thousand pages of testimony, Fisher presented Governor Edwin Stuart with a report that urged the attorney general to begin criminal proceedings against responsible persons. The Capitol Building graft scandal outraged the public, but the report leading to indictments for fraud and collusion helped to place Fisher on the side of justice and public trust.

Fisher was also becoming wealthy in business. As a founder and lifetime board member of Indiana Savings and Trust Company, he was pivotal in assisting New York Central Railroad in the purchase of coal lands in Indiana and surrounding counties. Fisher helped found the town of Clymer as a community for miners and, as president of the Dixon Run Land Company; lots were sold to the Pennsylvania Coal and Coke Corporation. Fisher and associates also started the Clymer Brick and Fire Clay Company, a supplier for many of the buildings in Clymer and Commodore, but later selling the brick works. By 1911, Fisher was president or director of Indiana Savings, the brick company, and the land company, as well as an electric company, the Pennsylvania Good Roads Association, vice president of Indiana Hospital, general counsel for New York Central Railroad, and vice president of the Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation. By 1919, he added to his credit presidencies of Beech Creek and Beech Creek Extension Railroads, subsidiaries of the New York Central, and director of Juniata Public Service [electric] Company. His business, law, and political experiences led Governor William Sproul to appoint Fisher as the state's banking commissioner in 1919 and to a commission that studied possible revisions to the state constitution.

Fisher considered running for governor in 1922, but withdrew from the race and campaigned for Gifford Pinchot, a support that surprised Governor Sproul and Republican Party bosses who were backing George E. Alter. Four years later, Fisher gained key support from the influential Joe Grundy, a Bucks County millionaire. Grundy disliked the powerful Philadelphia politician William S. Vare who was pushing Edward Beidleman, the lieutenant governor. Former governor John K. Tener and Thomas W. Philips, a wealthy Butler County oilman, competed in the Republican primary  Fisher was widely popular because of his publicized fight against the Capitol Building graft, endorsements by churches for his moral and pro-Sunday Blue Laws stand, support from farmers because of his farm boy background, his fight for child labor legislation while Senator, a pledge to sever his business and trusteeship connections (a promise he kept), and his campaign speeches supporting strong workmen's compensation and better working conditions. Voters were not persuaded by party bosses who tried to paint Fisher as a wealthy, anti-labor businessman. Fisher carried fifty-seven counties and a controversial victory. Beidleman had led in the vote count due to strong support in the Philadelphia region until votes were counted in Allegheny County. Vare's organization charged that there was vote fraud, but a Pittsburgh judge ruled against them and Fisher was declared the winner 641,934 votes to Beidleman's 626,640. The Republican primary proved to be the real political battle that year because Fisher crushed his Democratic opponent, Philadelphia Judge Eugene C. Bonniwell, in November by an unprecedented three to one margin and became the first governor in state history to receive more than one million votes.

Fisher was widely popular because of his publicized fight against the Capitol Building graft, endorsements by churches for his moral and pro-Sunday Blue Laws stand, support from farmers because of his farm boy background, his fight for child labor legislation while Senator, a pledge to sever his business and trusteeship connections (a promise he kept), and his campaign speeches supporting strong workmen's compensation and better working conditions. Voters were not persuaded by party bosses who tried to paint Fisher as a wealthy, anti-labor businessman. Fisher carried fifty-seven counties and a controversial victory. Beidleman had led in the vote count due to strong support in the Philadelphia region until votes were counted in Allegheny County. Vare's organization charged that there was vote fraud, but a Pittsburgh judge ruled against them and Fisher was declared the winner 641,934 votes to Beidleman's 626,640. The Republican primary proved to be the real political battle that year because Fisher crushed his Democratic opponent, Philadelphia Judge Eugene C. Bonniwell, in November by an unprecedented three to one margin and became the first governor in state history to receive more than one million votes.

Once Fisher was in office, there was a call to end primaries and return to the old convention system. They reasoned that forces like Vare's organization, political enemies of Fisher and Governor Pinchot, would have been defeated in a convention setting. However, as senator, Fisher had been a sponsor of legislation creating the state primary and he instead opted to push for election reforms to reduce the chances of ballot fraud. Fisher also battled Vare's sister-in-law, state Representative Flora M. Vare, when he defeated her proposal for a constitutional amendment giving everyone over age sixty-five a dollar per day pension. Fisher projected the annual cost of such a pension $36.5 million, which he said would have to be taken away from education.

While Fisher was not regarded as a skilled politician, he was admired as a good governor. Governor Fisher concentrated on a sound fiscal policy and public works construction, which earned him the nickname as "the Builder." New legislation authorized the governor to create the state Department of Revenue; form a Securities Commission under the Department of Banking; strip financial powers from the Department of State and Finance and change the name to Department of State; create the State Farm Products Show Commission to conduct the annual Farm Show; and reorganize the Department of Internal Affairs. With less waste in the use of tax dollars, Fisher was able to direct revenues to improve the state's normal schools; build 4,000 miles of new roads; build a new hospital for the mentally ill; add 450,000 acres to the state forest lands; acquire the Indiantown Gap military reservation; adopt the use of voting machines; enlarge the scope of the Pennsylvania Historical Commission; and build the State Farm Show Building and the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Bridge in Harrisburg. Fisher also instituted reforms in worker's compensation and floated a 59 million dollar bond to build welfare institutions.

There was a major labor strike in the soft coal regions between April 1927 and July 1928, but eighty-seven coal companies were convinced to stop using the generally hated Coal and Iron Police who enforced company interests, often brutally. Fisher signed legislation limiting their power, but after his term, he regretted not abolishing their authority. Fisher also attempted to restore unity in the Republican Party, but some members of the U.S. Senate launched a political attack upon the governor, stirring national attention. Fisher amended Governor Pinchot's scathing certificate of election in 1926 in which Pinchot said that Vare's election was "partly bought and partly stolen." This led to a Senate investigation and denial of a senate seat to William Vare. Fisher wanted Vare to be seated, but instead, this prompted a vicious attack on Fisher led by Senator Gerald Nye of South Dakota in which Fisher was also accused of buying his election. A barrage of verbal attacks was renewed in 1929 against Fisher when he appointed Joseph Grundy to fill the vacant senate seat caused by the Vare denial. Senator Nye vowed to block the Grundy appointment even though Grundy had bi-partisan support in Pennsylvania. Fisher angrily referred to some senators as "degenerates" and both Grundy and Fisher denounced senators who opposed Grundy as "narrow visioned." The Senate backed down and voted to seat Grundy with no dissenting votes. However, Grundy lost the next election and Fisher grew less supportive of Grundy.

Fisher left office at the highest point in his popularity and before the Great Depression fully impacted Pennsylvania. After his term, Fisher returned to private business and was a consultant to his son Robert's law firm. He was also president of the Pennsylvania Society of the Sons of the Revolution, chairman of a fire insurance company in Pittsburgh, director of two banking institutions in Indiana, and a board member of Indiana Hospital, the State Normal School, and Pennsylvania State College (later the Pennsylvania State University).

John S. Fisher died in Pittsburgh on June 25, 1940, and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Indiana, Pennsylvania.

Pages in this Section

- 1876-1951

- John Frederick Hartranft

- Henry Martyn Hoyt

- Robert Emory Pattison

- James Addams Beaver

- Daniel Hartman Hastings

- William Alexis Stone

- Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker

- Edwin Sydney Stuart

- John Kinley Tener

- Martin Grove Brumbaugh

- William Cameron Sproul

- Gifford Pinchot

- John Stuchell Fisher

- George Howard Earle

- Arthur Horace James

- Edward Martin

- John Cromwell Bell Jr.

- James Henderson Duff