Contact Period

Frontier is defined as "the border land" between two different groups of people. Four hundred years ago, Pennsylvania's frontier was the boundary region between Europeans and Native Americans. Initially, the two groups were mainly separated but exploiting each other for mutual gain. This was followed by a brief period, when Native Americans and Europeans occupied the same region but there continued to be a significant cultural boundary between them. However, as Europeans increased in numbers, the frontier moved west and so did most of the original residents of the land we call Pennsylvania.

In archaeological jargon, this time of European - Native American interaction is called the Contact Period. It covers the interval from European contact with Native Americans to the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Simply said "contact" means any interaction between Native Americans and Europeans. Frequently this took the form of stories of great ships, men riding strange creatures, exotic goods such as beads, brass kettles or flintlock muskets and, unfortunately for the Native Americans disease and warfare. It was a period of cultural transition, fragmentation and eventual collapse of Native American cultures in Pennsylvania.

The three major drainages of Pennsylvania were each occupied by distinct Indian tribes. We do not know what they called themselves at the time of contact but today they are known as the Delaware, the Susquehannocks, and the Monongahela. Each of these Indian groups interacted with the Europeans and European influences in a different fashion and, in each case, the short-term results were strikingly different. Thus the Contact Period was different in each drainage.

The Monongahela - a brief period of contact

The Monongahela were gone by the time European explorers entered the valley around 1635 AD and much of the region was unoccupied. The demise of the Monongahela is somewhat of a mystery. European glass beads are found at some villages, so the Monongahela culture was in contact with Europeans, but probably only through Native American middlemen. We have no written accounts of Europeans ever meeting these people and there is no direct evidence of catastrophic warfare among Monongahela villages. As elsewhere in the New World, European diseases likely decimated these people prior to ever meeting the Europeans.

One of the last non-stockaded villages of the Monongahela Culture, Foley Farm, located in Greene County, was a crowded settlement with many people. Archaeological excavations identified a large centrally placed petal-shaped building likely used for ritual/communal activities surrounded by as many as 50 houses. The Contact Period in western Pennsylvania was short and catastrophic for Native Americans. Few of them ever saw the cause for their disappearance.

Farming Villages in the Susquehanna Valley at the time of Columbus

When Columbus was exploring the Caribbean Islands in 1492, the Shenks Ferry Culture occupied the Susquehanna Valley. Beginning around 1550 AD, the Susquehannock Indians appeared in the Lower Susquehanna Valley and the Shenks Ferry people disappear. It is not known if the Susquehannocks conquered the indigenous Shenks Ferry culture, incorporated them into their own culture or that the Shenks Ferry people simply moved elsewhere. The Susquehannocks were Iroquoian speakers and shared many similarities with the Iroquois in New York.

The Susquehannocks and the start of the fur trade

One of the first recorded accounts of contact between Europeans and Pennsylvania Indians was in 1608 on the Chesapeake Bay between the Susquehannocks and John Smith of the Virginia Colony. He was very impressed and described them "as great and well-proportioned men, are seldom seen, for they seemed like Giants to the English". Based on archaeological evidence, we now know that they were no taller than the average modern day European however, they were a formidable tribe that had taken control of the Susquehanna Valley.

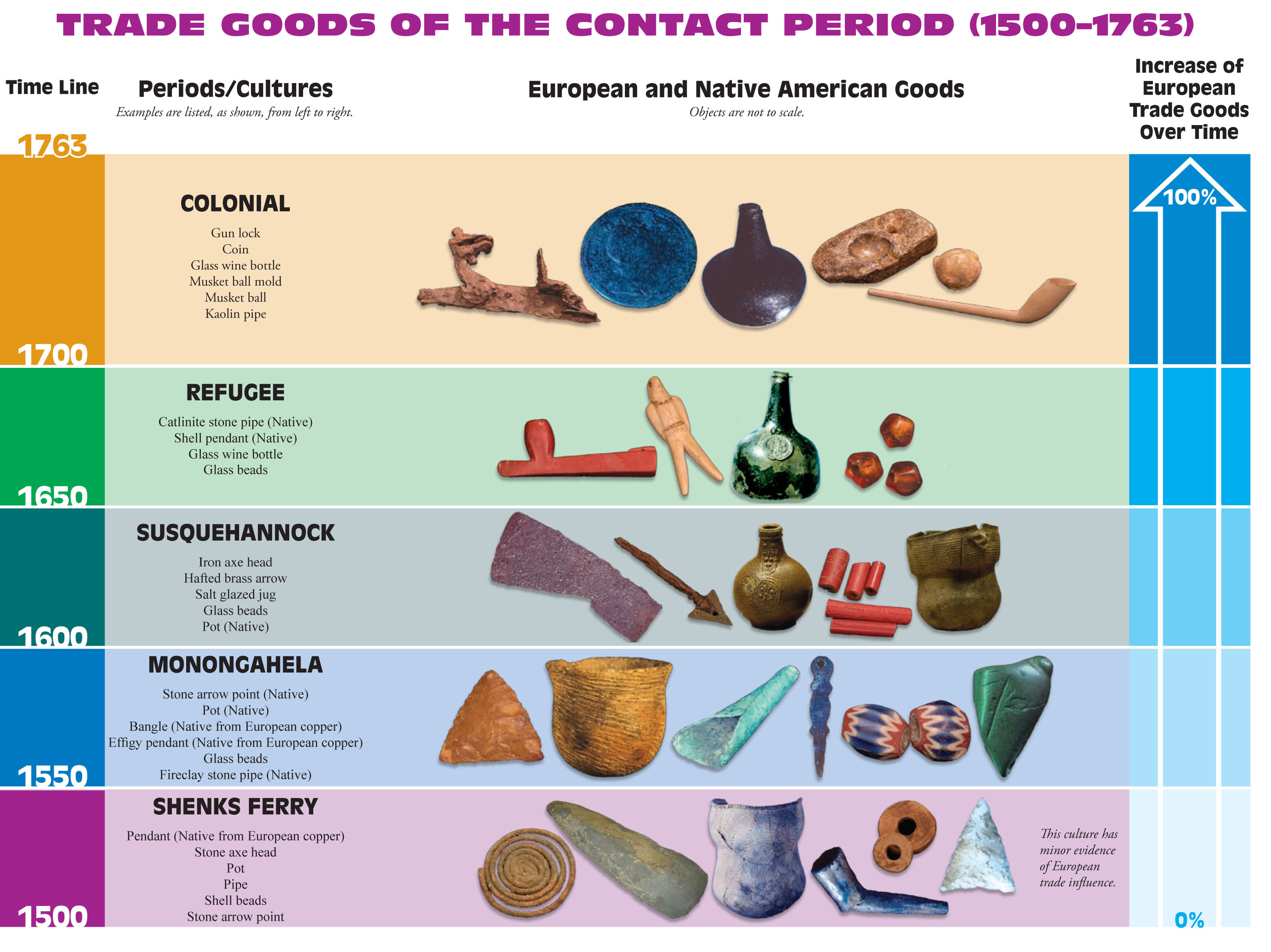

In contrast to the Shenks Ferry, the Susquehannocks lived in longhouses and practiced matrilineal descent. The Schultz Site is the earliest known Susquehannock village in the lower Susquehanna River Valley. The site is located along the Susquehanna River, south of the village of Washington Boro and it is estimated to have been occupied between 1575 and 1600. Housing perhaps as many as 1300 persons, the stockaded village is twice as large as any of the village sites of the preceding Shenks Ferry people. European trade items represent a relatively small portion of their artifacts suggesting that the fur trade was just beginning in the late 1500's. This site documents the beginning of the fur trade and the early effects of European Native Americans interaction.

The first Europeans must have been a perplexing image to the Indians. Native Americans desired European technology but were frequently frightened or abhorred by the Europeans and their culture. In most cases, the desire for European goods prevailed over their fears and in the early 1600's, a booming exchange of native furs for European goods began to take place. In fact, the Susquehannocks may have originally moved south from their homeland in New York State to better control the fur trade from competing native groups. However, once in the lower Susquehanna, they quickly trapped out their own territory and began to trade with Indians in Ohio, New York and Canada. These groups soon became jealous of the Susquehannocks "middle - man" position and much of the early Contact Period was characterized by inter-tribal warfare over control of the fur trade: the so-called Beaver Wars.

Throughout the 1600s, the Susquehannocks lived in large fortified villages, some of which may have contained as many as 3,000 people. The villages were composed of longhouses that were 60 - 80 feet in length and housed a number of nuclear families related through the female line. The Susquehannock homeland was along the Susquehanna River especially in Cumberland, Dauphin, Lancaster and York counties. The Susquehannocks engaged in extensive trading with the English, Dutch, and Swedes, receiving goods such as glass beads, iron axes, metal harpoons, brass kettles and flintlock muskets. By 1650, much of their natural technology had been replaced by European technology.

The Seneca of western New York were especially concerned with the Susquehannock control of access to the Europeans and several large-scale battles were fought between them and Susquehannocks. The Strickler village site, also in Washington Boro, probably is the site of one of these engagements. The site dates from the 1640s to about 1665. The village was over 12 acres in size, with a population of about 2,900 residents. Like most Susquehannock villages, Strickler was stockaded. However, this site is notable in that European-style bastions were constructed on at least two of the stockade's corners. European goods from this site document the acculturation of the Susquehannocks with most of their material remains being European in origin. Strickler was troubled by warfare and competition with the Iroquois over the fur trade, and an unstable relationship with Europe's new Maryland colony.

Although the Susquehannocks controlled the fur trade for nearly a century, they were in constant conflict with other Indian tribes, especially the Seneca of western New York. Large -scale battles took place with the Seneca in Washington Boro and across the river in York County. The warfare and disease eventually caught up with them. By 1675, the Susquehannocks had been decimated by several epidemics and were finally driven out of the valley by the Seneca. A small population of approximately 500 moved to Maryland, but eventually returned to the Susquehanna Valley by the 1690's. The Seneca were concerned with the vacuum created by the defeat of the Susquehannocks and invited them back as a buffer between the Iroquois homeland and the English. In the early 1700's the newly established American colonial government gave them land in Conestoga Township, Lancaster County, effectively creating one of the first Indian reservations in Pennsylvania. The Susquehannocks became known as the Conestoga Indians and frequently worked for the residents of Lancaster County.

The Delaware and William Penn

Although the archaeology of Delaware Valley has been extensively studied, the late prehistoric and Contact Periods are not well understood. Specifically, the evidence relating prehistoric cultures to the historic Lenni Lenape (a.k.a. the Delaware Indian tribe) is tenuous. It is believed the prehistoric cultures that archaeologists have named Overpeck and Minguannan are the ancestors of the modern Lenni Lenape however this is still debated. William Penn arrived in the Commonwealth in 1682, and in his charter he was required to "reduce the Savage Natives by gentle and just manners to the love of civil Societies and Christian Religion". He instituted a different policy compared to some of the other colonies. For the Europeans, the essential goal in dealing with the Indians was to acquire their land. In most cases, whatever the official strategy, the result was warfare and Native people were killed or forcibly removed. In Pennsylvania however, the policy was to treat them fairly and buy their land. This was accomplished through a series of treaties and by 1792, Penn and his decedents had purchased all of what is now known as Pennsylvania.

The Delaware were the first Native groups to be affected by Penn's policy of "fairness and equality to all". Generally, William Penn was well respected by the Delaware, but his agents and descendants were not. The concept of "buying land" was foreign to most Native Americans and many were left bitter and angry by this practice. In particular, the famous "Walking Purchase" of 1737 enraged the Delaware from an already embittering feeling that they had been pushed from their lands. They moved to western Pennsylvania for a time, but by 1800 they had been displaced to Indiana. The main groups are currently living in Oklahoma and Ontario.

Peace Followed by Conflict

Penn's policies created a time of relative peace and the competition for furs and European goods had essentially passed to the west by the early 1700's. The remaining Susquehannocks resided at Conestoga Manor in Lancaster County and many Delaware had moved west or to the Wyoming Valley above the forks of the Susquehanna. Encouraged by the Seneca, many small refugee groups such as the Tuscarora, Shawnee, Nanticoke and Tutelo moved into the Commonwealth. Southeastern Pennsylvania became a mixture of Indians outnumbered by European settlers.

Mathew Patton was one of these early settlers who began a farm in the 1740's in Franklin County. He was doing so well that he undertook the building a second house when a new conflict began. As France and England began to expand their lands in North America, the inevitable conflict between the two European super-powers began.

In response to English intrusions in the Upper Ohio valley, the French built a series of forts in western Pennsylvania. Two such forts were Fort LeBoeuf south of Lake Erie and the famous Fort Duquesne at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers. The war began as a result of an expedition led by George Washington. In 1754, he was sent by the Virginia Colony to attack Fort Duquesne. On his way, he encountered a French patrol, a fight ensued and the brother of the French commander-in-chief was killed. Washington knew he was in trouble and hastily built Fort Necessity (in Westmoreland County) as a defense against an overwhelmingly larger French force. Unfortunately, he picked a boggy site and it rained during the battle causing his troop's muskets to misfire and he was forced to surrender. This was the site of the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

When news reached Great Britain, General Braddock was sent to the Ohio Valley with 2100 troops to destroy Fort Duquesne. Eight miles from their objective, Braddock was attacked on July 9 1755 by a smaller but aggressive force of French and Indians. Within five hours the British suffered over 800 casualties. Braddock was mortally wounded and his army was routed. The catastrophic defeat left settlers of western Pennsylvania unprotected and allowed the Indian allies of the French to initiate a series of raids on settlers in both western Pennsylvania and the Susquehanna Valley

The French and Indian War served to unify a variety of displaced and fragmented Native American tribes who shared frustration and anger for the Europeans. Initially, the Delaware were undecided but with intimidation from the French, they eventually took up the hatchet against the English. In one of their early raids, they attacked a series of communities in Franklin and Fulton Counties, killing and capturing more than 100 people. Mathew Patton's farm witnessed one of these attacks and was burned to the ground.

After Braddock's defeat and several Indian raids, the British built a series of forts along the Susquehanna river. The largest of these was Fort Augusta at Sunbury, with earthen bastions and walls over 200 feet long. Fort Halifax and Fort Hunter, established down river from Augusta as supply forts, were positioned because the British felt the war would be fought along the West Branch of the Susquehanna River.

As it turned out, most of the fighting took place in the Ohio Valley. In 1758, with a command of 7000 troops, General Forbes set out to retake Fort Duquesne. He built a road from Carlisle to the forks of the Ohio that included the major forts of Bedford, Ligonier and Pitt. Fort Loudoun served as an important supply depot during this campaign that eventually removed the French from western Pennsylvania. Built in 1756, it is located in Franklin County on the site of Matthew Patton's farm. The design was an interesting adaptation by the Pennsylvania Quaker government to implement a typical English fortification. It included one of Patton's houses as the officer's quarters. The fort was never attacked, but it was the scene of a rebellion in 1765 by local citizens against the harsh treatment by the British garrison. This action is an example of the frustration faced on Pennsylvania's frontier in the mid 1700's and some consider this the first act of the American Revolution.

With the Ohio Valley secure, the British invaded Canada and captured Montreal in 1760. This effectively ended the war on the North American mainland. Known in Europe as the Seven Years' War, it ended in North America with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, February 10, 1763. The Indian allies of the French were dissatisfied with the treaty and offended by the post-war policies of the British. Ottawa chief, Pontiac, led a series of attacks in the Ohio Valley in May, 1763, destroying eight forts and killing thousands of soldiers and settlers. On August 6th a large Indian force was defeated by Colonel Bouquet at the Battle of Bushy Run, ending Pontiac's Rebellion.

As part of the violence, the infamous "Paxtang Boys" from Harrisburg attacked the remaining Susquehannocks (now known as the Conestoga's) at Conestoga Manor. The survivors were placed in the Lancaster jail for their own protection, but two days after Christmas the Paxtang Boys returned and killed every man women and child, thus ending the Susquehannock culture. During the Revolutionary War, additional savagery was committed by both Native Americans and Colonial forces in the Wyoming Valley and this signaled the end of Native American habitation as tribal groups in most of Pennsylvania.

In most of the original colonies, after the Indians had been decimated by disease and warfare, they were given land; these were the first Indian reservations. With a few exceptions, Pennsylvania did not follow this policy and felt that buying their land was sufficient payment to fulfill their humanitarian duties. The last Native American land in the Commonwealth was the so-called Cornplanter Grant which consisted of 600 acres along the Allegheny River, near the New York border. This reservation was occupied by Cornplanter, his descendants and other Indians until 1964 when the remaining residents were relocated upstream for the construction of the Kinzua Dam project. The dam project was strongly opposed by Native Americans and signaled the beginning of a revitalization of Native American Culture in America. Although, there are not any officially recognized Native American lands in the Commonwealth, many Indians continue to occupy the state. There have been several attempts to create Indian land for the Delaware, but the Commonwealth has opposed such initiatives by using the original land treaties as proof of ownership.