Early and Middle Woodland Period

By 2,850 BP., the climate returns to warm and wet, similar to that of today. Trade and a few of the characteristics of the Transitional Period tool kit continued for a short time into the Woodland Period but were no longer in evidence by 2,700 BP. Projectile points are notched or stemmed. Stone tools were again made mostly from locally available material, rather than from metarhyolite or jasper.

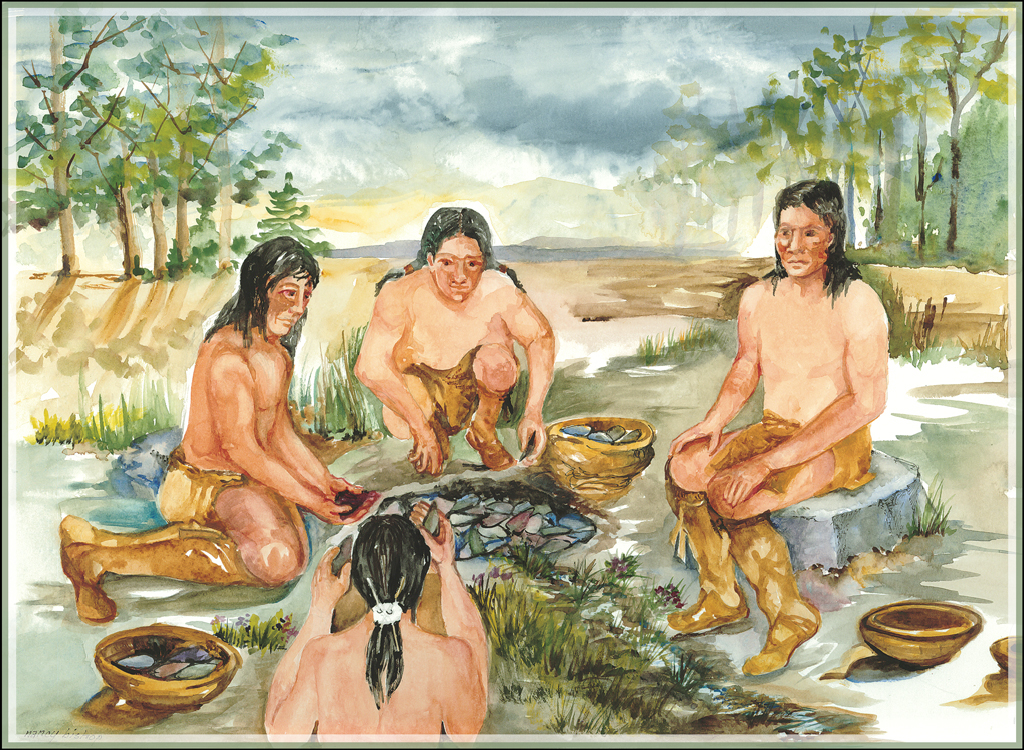

The first pottery made in Pennsylvania was hand molded, with small handles, flat bottoms, and plain surfaces. In some cases, the bottoms show impressions from being shaped on some kind of woven mat. These earliest pots seem to be crude, ceramic copies of soapstone bowls. Slightly later vessels were built up of slabs or coils of clay and conical in shape. They were welded together with a wooden paddle wrapped with cord or string, which left impressions of the cordage on the outside and sometimes the inside of the pot. Although seemingly fragile, pottery vessels probably represent a significant change in the processing and storage of food resources.

The use and production of pottery, which is difficult to transport, suggests fewer base camp movements and more permanent settlements. Early Woodland groups probably continued to move on a seasonal basis, but base camps in favorable environments may have been occupied for longer periods of the year. From these base camps, work groups may have been sent out to harvest wild plant foods such as seeds or nuts, and to hunt deer, water fowl, and other game. Although the evidence is not conclusive, there are a few examples of what appears to be domesticated squash and maygrass. These plants may have been commonly grown in gardens in eastern Pennsylvania during Early Woodland times.

Early Woodland roasting pit with heat reddened soil, charcoal, and fire-cracked rock. Photo courtesy of KCI, Section of Archaeology collections.

In the Ohio Valley of western Pennsylvania, more dramatic developments took place, including the use of burial mounds and elaborate burial ceremonies. Archaeologists call this the Adena culture, which is part of a regional development that extended from the Upper Mississippi Valley. Adena people lived in round houses clustered in small hamlets. They continued to hunt and fish but they intensified their use of wild plant foods. There is good evidence that they gathered seeds from sunflower and chenopodium (lamb's quarters) and ground them into a flour. There is also evidence for the use of squash, which was domesticated in Mexico and was gradually transported to Northeastern North American. It is likely that some or all of these plants were grown in gardens as a mechanism to supplement the gathering of wild foods.

An Early Woodland burial mound, many of which have been destroyed by modern development. (Photograph courtesy of the Section of Anthropology, Carnegie Museum of Natural History.)

By 2,000 BP., the beginning of the Middle Woodland period, there seems to have been a significant drop in population based on the number of archaeological sites in Pennsylvania and throughout the Middle Atlantic region. However, this apparent drop in population may have more to do with our inability to identify Middle Woodland artifacts than the actual decrease in human population. Based on carbon 14 dates, people lived in Pennsylvania during this period, but they did not use a distinctive assemblage of artifacts that could be distinguished from Early Woodland or Late Woodland artifacts. The artifacts of the Middle Woodland are rather nondescript in appearance, and even their pottery is usually not distinctive. The few sites that have been excavated are small, and fire-cracked rock features are no longer common. Trash pits, suggesting more permanent occupations, have been found, but they are rare. Some of the fired clay pottery is covered with net impressions rather than cordmarking and some has distinctive designs along the rim but most is undecorated. The spear points are notched or stemmed and generally not distinctive in their shape. Although little is known about the Middle Woodland period, this was probably a very interesting time in Pennsylvania prehistory, during which people became more settled and more dependent on domesticated plant foods.

In the Ohio Valley of Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio, an expansive trade network developed in the Middle Woodland, which archaeologists call the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. The network extended from the Gulf of Mexico to Yellowstone National Park to the Delaware Bay. Trade items included marine shells, ocean turtle shells, shark and alligator teeth from the Atlantic and Florida coasts; copper and silver from the Great Lakes region; and obsidian, a volcanic glass from the western United States. Ceremonial artifacts, especially those from long distance trade, were placed in the burials of high-ranking individuals. The trade network was associated with a pattern of burial ceremonialism and mound complexes that existed throughout the Upper Ohio Valley. Hopewell people were true horticulturists, growing corn and squash and living in settled hamlets.

Hopewell pottery, hamlets, and burial mounds have been found in western Pennsylvania, but these characteristics are less common than in the region to the west. Hopewell in western Pennsylvania likely ended at approximately 1450 BP. Small horticultural groups continued in the area, but without the Hopewellian pottery styles and trade connections.

The Early and Middle Woodland periods were probably very dynamic, with significant technological, social, and religious developments. However, our understanding of these developments is very poor. The answer to these questions will require a great deal more excavation, especially at buried sites that have been protected from modern development.

For more information on ceremonial earthworks and burial mounds, visit the Hopewell Culture National Historic Park website.