Paleoindian Period

Settling of the New World

Human biological evolution began in the Old World, and Native Americans are relatively recent arrivals to the New World. Their physical resemblance to the people of East Asia has long been recognized. More specifically, based on similarities in language, teeth, and DNA, there is nearly unanimous agreement that the ancestors of the Native Americans originated in Asia. It is also generally agreed that they migrated to the New World along or through the Bering Strait Land Bridge. The land bridge connected Siberia with Alaska and would have included the Aleutian Islands. The huge land mass was created when sea levels dropped 100 meters because so much of the earth’s water was locked up in the glaciers.

In 1999, Dennis Stanford and Bruce Bradley proposed an Atlantic crossing and a European origin for Native Americans. Their argument is based on technological similarities between European Upper Paleolithic artifacts and 13,000 year old Native American artifacts. However, these similarities are probably the result of parallel technological developments rather than cultural connections. Although many archaeologists would concede that transatlantic sea travel may have been possible 18,000 years ago, there is little other supporting data for a European origin, and the majority of archaeologists continue to support a migration from Asia.

The hot debate is the dating of the entrance and the exact route into the New World. During the Ice Age, Canada was covered by two glaciers; one covering the Rocky Mountains and one centered on Hudson Bay. The first immigrants may have come down from Alaska along a route east of the Rocky Mountains through an "ice free corridor" between the two glaciers. Another possibility is that they came down along the west coast of Canada by boat. However, there are problems with demonstrating either of these scenarios. The problem with the "ice free corridor" route is that the corridor did not open until about 13,000 years ago. For much of the year, it would have been filled with melt water from the adjacent glaciers and rather inhospitable. Further, the melt water would have washed away most camp sites that may have formed in this region. The coastal route is equally hard to demonstrate because the ice age coastline is at least 30 meters under water because melting glaciers caused a significant rise in sea level. The coastal route is currently favored because many of the earliest sites are near the Pacific coast in North and South America.

Clovis First vs. Pre-Clovis

Dating the entrance is also hotly debated, and it is not simply a matter of who has found the oldest site. This is a very significant anthropological issue, representing a question of how humans occupy a new land and the rate of their migration. Is it done quickly or slowly? Do humans occupy the areas with the most resources first, hop-skipping across the continents, or do they move in a continuous wave, filling the regions evenly? Has the incredible variety of Native American cultures and languages been created in 12,000, 18,000 or 30,000 years?

There are hundreds of well-dated sites in both North and South America that date to between 11,700 BP. and 13,100 BP. Most of these sites contain spear points with a flute, or channel along its length; in North America, the earliest style of fluted points is called Clovis. Based on the relatively large number of sites from this period, some archaeologists argue that humans crossed the Bering Strait Land Bridge at about 14,000 BP. and quickly occupied all of North and South American by 12,500 BP.; thus, moving 7,000 miles from the central United States to the tip of South America in 2,500 years. This is called the Clovis First model and usually includes a provision called the "overkill hypothesis" proposed by Paul Martin in 1973. He proposed that the megafauna (for example, mammoth, mastodon, and musk-ox) of the New World were not familiar with humans as predators and therefore were quickly exterminated as humans migrated south. In fact, the justification for the rapid movement by humans across the continent is their search for food in the form of big game animals.

Other archaeologists argue that this is much too rapid for human migration, especially considering that they had to cross several significantly different environmental zones between Alaska and the tip of South America. These archaeologists contend that humans entered much earlier, at 21,700-34,300 BP., and slowly filled the New World. This is called the Pre-Clovis model. This group of archaeologists also does not support the "overkill hypothesis" and presents alternative data that maintains both environmental change and human predation contributed to the extinction of the megafauna.

Pennsylvania has been at the center of this controversy since the 1970s with the excavation of the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Washington County, Pennsylvania. This site dates to at least 19,400 BP. and contains artifacts that are similar to those being found in Siberia at about the same time. Recently, several other sites have been discovered, such as Cactus Hill in Virginia (19,300 BP.), Topper in South Carolina (14,800 BP.), Buttermilk Creek in Texas (18,730 BP.), Page Ladson in Florida (17,550 BP.) and Monte Verde in Chile (14,000 BP.). These obviously add support to the early dates of Meadowcroft and represent evidence of an early migration. Because there are so many sites dating to the period from 12,500-13,400 BP., it is hard to imagine that they would have appeared so quickly without a Pre-Clovis population in place. Most archaeologists now favor the Pre-Clovis model, but the debate continues.

Paleoindian Lifeways

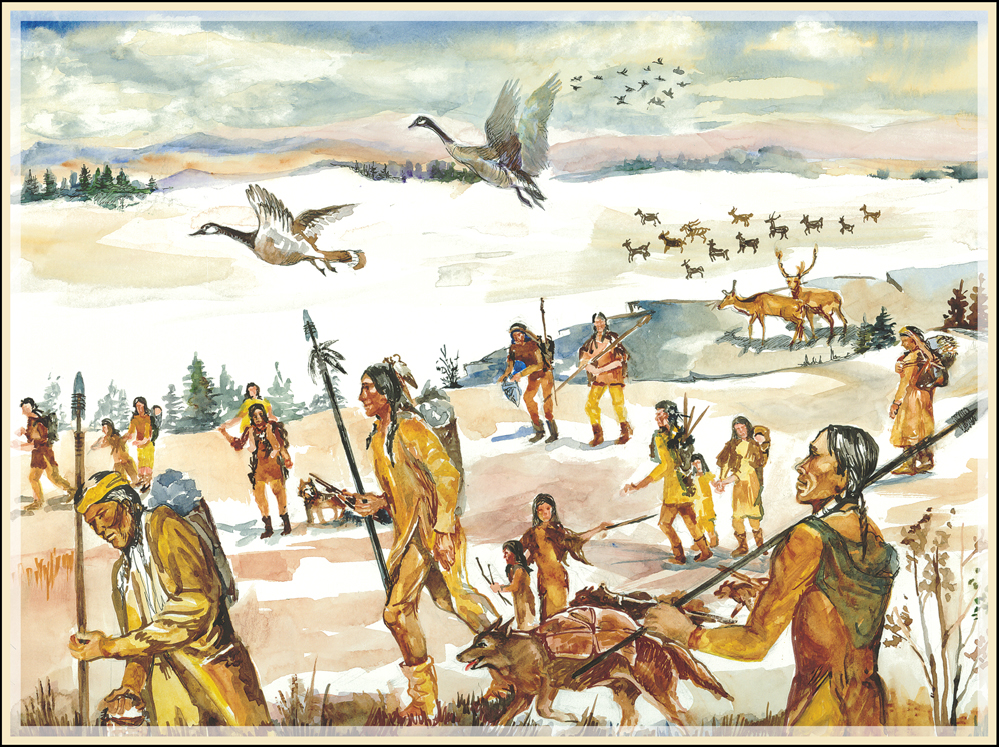

During the Pre-Clovis period, glaciers covered northern Pennsylvania, but southern Pennsylvania was characterized by a patchwork of forest and open grassy environments. The foods available to humans included mammoth, mastodon, musk-ox, horse, camel, moose, caribou, elk (all termed megafauna because of their size), small mammals, seeds, nuts, and berries. Based on evidence from the Meadowcroft Rockshelter, human population density was very low, and family groups or bands moved frequently to exploit these foods. Because there were more than sufficient food resources, special tools to exploit this environment were not needed. Stone tools included simple flake knives and scrapers, some of which were long, narrow blades, as well as pieces chipped into leaf-shaped tools that served as knives and probably also as spear points. Because the Pre-Clovis technology is not very distinctive and human population density was very low, sites from this time period are difficult to identify and are very rare. Meadowcroft Rockshelter is the only one found so far in Pennsylvania.

Around 13,100 BP., a new and distinctive spear point style was invented in North America. It is called a fluted point because of the flute or channel down the length of both sides of the spear point. The groove likely facilitated the hafting of the spear point to the spear shaft. It is one of the most difficult spear points to make, and fluting is not found anywhere else in the world. Fluted points called Eastern Clovis are found in Pennsylvania dating to around 12,900 BP. There are several styles (called types by archaeologists) of fluted points and these change shape over time. The earliest is Clovis and later types are called Debert, Barnes, Crowfield and Plano.

Fluted Points from the Shoop Site

Compared to latter groups, Paleoindians seemed to have preferred the highest quality stone to make their tools. Although they also used lesser quality material, Clovis spear points, knives, and scrapers were usually made from the best stone in the region such as cherts and jaspers. By tracing the sources of this stone, archaeologists are able to map the general movements of Paleoindian peoples, and they frequently range over 200 miles per year.

There has always been some debate concerning the Paleoindian diet. In the western United States, there is good evidence that they ate mammoth, mastodon (forms of wooly elephants), bison, horse, and camel. They also hunted a variety of smaller animals and ate a wide variety of plant foods, but at least part of their diet was based on now-extinct animals. In the East we do not have much data to address the issue of diet, but Pennsylvania has one of the few sites that does. The Shawnee-Minisink site, located along the Delaware River in Monroe County, is one of the few deeply buried Paleoindian sites in the East. It contains many tools and two fluted points dated to 12,800 BP. based on carbon 14 dating. Most significantly, one of the cooking hearths contained a variety of seeds, hawthorn plums, blackberries, and fish remains. There is little evidence that Paleoindians hunted any extinct animals such as in the western United States. Paleoindians were hunters but they focused on caribou, elk and deer. The Shawnee-Minisink site is probably more representative of their daily diet.

Paleoindian Tools from the Shoop Site

Clovis people in Pennsylvania moved their camps in a seasonal pattern or "round" to the locations of predictable food resources, such as along the migration routes of caribou, water fowl, or anadromous (spawning) fish. In contrast to the Shawnee - Minisink site, the Shoop site in Dauphin County suggests another type of subsistence pattern. The artifact assemblage at the Shoop site is actually more similar to sites in New England and southern Canada than most other sites in Pennsylvania. The tool kit from this site was made from a stone only found 250 miles away to the north in western New York State. There are at least 11 concentrations of artifacts at this site, and it is believed that each represents a separate visit between western New York and central Pennsylvania. Approximately 100 fluted points have been recovered from this site, far more than any other site in Pennsylvania and more than most sites in the eastern United States. Their tools include many scrapers that were used for cleaning hides for clothing and shaping wooden tools and tool handles. It is hard to attribute the high numbers of spear points on a ridge top setting to anything else other than hunting. This site was probably situated on a caribou or elk migration route and was visited on an annual basis to hunt these animals.

Using a hand propelled spear to kill any large animal, let along mammoths or mastodons, would have been difficult, but also dangerous. One means of increasing hunting success was the use of the atlatl or spear thrower. This device consisted of a flattened, wooden stick with a hook at one end to launch the spear. It served to lengthen the hunter's throwing arm and increased the accuracy and speed of the throw. It would have worked well in the open forest of the Paleoindian period. Although this tool is traditionally associated with the Archaic Period, it is at least 25,000 years old in Europe. It was probably brought over with the first migrations into the New World. Although the wooden atlatl is not preserved on archaeological sites, it is very likely that it was used by Paleoindians.

The Paleoindian Period was an amazing time in Pennsylvania prehistory. The human groups were small, and they probably traveled for months without meeting anyone else. Based on what we know of other foraging cultures living in small groups, there was little conflict between groups, and when they met at a pre-arranged location, it was probably a time of celebration. Because each band consisted only of blood relatives and their spouses, meeting other bands was also a time for marriage ceremonies.

The Paleoindian Period closes with the end of the Ice Age and the emergence of a nearly modern environment, requiring humans to develop new strategies for acquiring food, resulting in new artifact assemblages. Archaeologists identify these new artifacts as being part of the Archaic Period.

The Paleoindian Period presents a fascinating opportunity for the anthropological study of very low-density populations adapting to what appear to be relatively abundant conditions. It documents how people occupy a new land and it also set cultural traditions that lasted for thousands of years. We are beginning to understand Paleoindian technology and diet but we have much to learn about their social organization and religious beliefs.

For more information on the populating of the American continents visit Journey to a New Land (SFU Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology).