Petroglyphs of Pennsylvania

Definition

Petroglyphs ("rock carvings" - From petro, meaning "rock" and glyph, meaning "symbol") -a form of rock art that consist of designs carved into the surface of natural rock. Forms include lines, dots, numbers, letters, human, animal, supernatural beings or astronomical images. They are found throughout the world and can date as far back as tens of thousands of years ago.

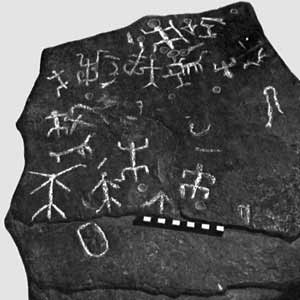

Although people often think of rock art as something found in the American Southwest, some of Pennsylvania's Native American Peoples also left a legacy of these images carved in stone. Most petroglyphs were formed using harder stones (direct percussion) or hammer-stones and stone chisels (indirect percussion). In soft sandstone they could be simply scratched into the surface (incised). Pennsylvania's petroglyphs are usually carved less than three eights of an inch deep, and grooves making up designs are less than an inch wide. Because of this the petroglyphs can be very difficult to see. They are best viewed when the sun is at a low angle to the rock, usually early or late in the day. Originally, some may have been decorated and painted, but except for one or two instances, (36CB28, Chickaree Hill Petroglyphs; 36EL3, Laurel Run Pictographs) there is no evidence remaining on those that can be seen today.

The images and designs found at petroglyph sites were probably common in prehistoric societies. Many were likely portrayed in wood, basketry and clothing. However, these types of artifacts practically never survive in the archaeological contexts of Eastern North America. Therefore, these images give us our only direct window into the minds of prehistoric humans. They are also unique in that many can be visited in the same place, in the same context, as when their makers created them.

Petroglyph Locations

There are less than 40 Native American petroglyph sites recorded in the Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey files (PASS). The majority of these are found in prominent locations, near water, especially larger rivers. The images can be found in clusters of a few to groups of hundreds. Rarely are petroglyphs found in upland settings.

There are nearly 30 sites recorded in the Ohio Valley although most of these are represented by small groups of images. In contrast, the lower Susquehanna River has the highest concentration of petroglyphs in the Northeast with only 10 sites but probably more than 1000 separate carvings. These are found within a 23-mile stretch running through southern Lancaster County to just below the Mason-Dixon Line. Because of the construction of hydroelectric projects on that portion of the Susquehanna, many of these petroglyphs have been submerged or removed for preservation.

It is interesting that there are very few examples in the Upper Susquehanna drainage or the entire Delaware drainage. There is probably a culturally determined geographical distribution to petroglyphs. In the Northeastern United States, there were two major Native American language groups - Iroquoian and Algonquian. The Iroquoian speakers were centered in what is now New York State and the eastern Great Lakes. They are surrounded by Algonquian speakers in New England and southern Pennsylvania. There are few petroglyphs in the land of the Iroquois and most of the images are more like Algonquian images than Iroquois images. One hypothesis holds that most of the petroglyphs were made by the Algonquians and petroglyphs were not a significant characteristic of Iroquois imagery.

Age

Petroglyphs are difficult to date. In Africa and Europe they can be tens of thousands of years old. However, in Pennsylvania, petroglyphs are likely less than 1000 years old. At any one site, they are usually of the same style and the markings do not exhibit any obvious differences in aging based on surface erosion of the rock. Some of the images are very similar to those used by historic Native Americans and therefore it is probable that they date within the recent past.

This relatively young age is in contrast to other parts of the world or even the Southwestern United States where they are likely much older. It may be that petroglyphs are generally associated with organized tribes and/or farming and this form of social organization and subsistence occurs relatively late in Pennsylvania.

Style

Most petroglyphs in Pennsylvania are similar stylistically to Algonquian art found throughout the Northern mid-west, Northeast, and into Canada. The bodies of petroglyphs east of the Allegheny Mountains tend to be fully-carved, while sites to the west include bodies that are carved in outline and sometimes even have designs carved within the bodies. Two remarkable exceptions to the general style are the Walnut Island and the Bald Friar sites, which are above and below the Algonquian-like petroglyphs at Safe Harbor on the Lower Susquehanna. Many designs at these two sites are unlike any others in the region.

Along the Allegheny River, Indian God Rock, below Franklin in Venango County, and the Parkers Landing petroglyph further south are some of the most interesting examples of petroglyphs in the Commonwealth. These contain many naturalistic designs and both sites contain spectacular supernatural - part human, part animal figures. The so-called "Water Panther" at Parkers Landing is a spectacular rendition of a common image in the Algonquian belief system. The Francis Farm and Sugar Grove petroglyphs in the Monongahela watershed are similar in style to those at Indian God Rock and Parkers Landing.

Many of the petroglyph sites on the Lower Susquehanna River are now submerged in lakes behind the dams on that part of the river. The Walnut Island site, situated near Washington Boro, is now under water impounded by the Safe Harbor Dam. Many of the petroglyphs there were salvaged for preservation by the Pennsylvania Historical Commission in the 1930's, which for the most part destroyed the site. The Walnut Island designs are very abstract compared to the more naturalistic designs at other Pennsylvania sites, and although in no way related, in some ways resemble characters like those in Chinese writing. Many of the petroglyphs on the island had been buried by many feet of soil.

In the area below just below Safe Harbor Dam the largest concentration of petroglyphs in the Northeastern United States still survives. The most famous of these sites, Big Indian Rock and Little Indian Rock, were first recorded in 1863 and were further investigated by Donald Cadzow of the Pennsylvania Historical Commission in 1930-31. In the 1980's petroglyphs were discovered on several other rocks in the vicinity, and in 2002 the Conejohela Chapter 28, Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology systematically recorded more than 300 petroglyphs on seven rocks along this stretch of the river. These petroglyphs consist of naturalistic designs of humans, animals, and their tracks as well as more supernatural depictions of human and animal-like imagery, and other conventionalized symbolic designs (circles, dots, etc.).

The Bald Friar petroglyph sites, just south of the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, are now under water impounded by the Conowingo Dam. These sites are characterized by carvings of concentric circles, "sun bursts", "stick figure trees", and peculiar "mask" or "stylized fish" designs.

Only one petroglyph site has been recorded on the Delaware River. The Jennings Petroglyph is a large rock containing more than 30 carvings that was found on the New Jersey side of the river across from Dingmans Ferry, Pike County. In 1965 it was removed to Seton Hall University to save it from being covered by the lake that was to be formed behind the Tocks Island Dam - a dam that was never built. Its designs resemble the imagery found at the Safe Harbor sites.

Interpreting the Meaning of Petroglyphs

Petroglyphs are a form of symbolic communication and their message was important. We now know that they are not a form of prehistoric graffiti as was widely believed in the past. For Native Americans to carve in rock with stone tools required too much effort to be done without serious intention. These locations were probably important, possibly sacred, places prior to the placement of the images. The petroglyphs probably formalized and verified their significance in the cosmology of Native American belief systems.

The petroglyphs conveyed information - perhaps describing tribal boundaries, hunting grounds, or served to describe the people who lived in or passed through the region. The prominent riverside petroglyphs such as Big Indian Rock in the Susquehanna River and Indian God Rock along the Allegheny River are perhaps plausible examples of the boundary marker theory. That said, there are many which are not obviously evident and must have had other functions.

Certain symbols are common on Native American petroglyphs in Pennsylvania. Naturalistic designs include humans, animals and birds, their footprints and tracks. Other, more symbolic designs include circles, spirals, and dots (cupules), as well as figures that can be described as human or animal-like but changed (anthropomorphic or zoomorphic), or even part animal, part human. Still other designs represent conventionalized religious, mythological, or supernatural symbols utilized throughout a large geographic and cultural area, such as manifestations of the Algonquian "Great Spirit" or Manitou - Thunderbirds (Pinasiwuk), Bear (Makwa), Wolf (Myeengun), Great Lynx, or Water Panther (Mishipizheu), or Horned Snake (Ginebik). There were many different Native American groups in Pennsylvania and their belief systems varied considerably. The meaning of a symbol to one group may have been very different to another group and some tribes may not have used petroglyphs at all.

Petroglyph sites were almost certainly sacred places where people came to communicate with the supernatural. Some sites may have been places where medicine men, community, or spiritual leaders went to meditate to receive visions or guidance to lead or heal their people. Some of the symbols may have had special significance for hunting or fishing or for solving family or tribal problems.

Further, some may have served as "teaching rocks". Young people may have been brought to these places to learn about their culture and the world around them - similar to religious classes that are conducted all over the world today. Some petroglyphs may represent animal or spirit "helpers" or totems that were received through a visit or a vision by a medicine man, or by an adolescent in a "coming-of-age" ceremony.

At Safe Harbor, some petroglyphs seem to have astronomical significance. The river and surrounding hills there create a magnificent setting for observing the sky and marking celestial positions. Six of the seven fully-carved (intaglio) snake symbols point to the sunrise or sunset positions for the equinoxes (equal length of day and night) or the solstices (longest and shortest days of the year). (The seventh resides within a unique grouping of designs enclosed within a circle). These times would mark planting and harvesting times as well as important turning points in the cycle of the year. All over the world, people have devised methods for calculating these days and it is not surprising that Native Americans did also. Other groups of dots may denote constellations, and one perhaps signifies a solar eclipse.

The petroglyphs of Pennsylvania probably served a multiplicity of functions. We may never fully understand their meanings - only catch glimpses of things that were incredibly important in the lives of the people who carved them.

Ethics and Visiting Petroglyph

sites Native American petroglyphs are sacred places. Many Native Americans consider petroglyphs sites as gifts from their ancestors, sacred; to be treated with the same respect as any other place of worship. To all of us, they are an irreplaceable part of our Commonwealth's cultural heritage and the story of this land.

Great care must be used when visiting petroglyph sites. Although some have been maliciously defaced, most visitors have treated them with respect. They may appear to be in good shape, but the rocks on which they were carved are susceptible to the destructive forces of nature and man. They should not be walked on with shoes. They should not be colored with paint, chalk or crayons or any other medium. Many have been copied with plaster or latex molds but these are dangerous procedures that can easily damage the petroglyphs. The best way to record the images is to photograph them under good lighting conditions (when the sun is at a low angle to the rock surface - usually early morning or late in the day)

Recording Petroglyph Sites

Petroglyphs can be easily overlooked, and as a result there are undoubtedly still sites in Pennsylvania waiting to be found. Petroglyphs are a very significant type of archaeological site. They need to be protected and shared with all citizens. If you find a petroglyph please alert the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC). Recording the site with the Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey (PASS) is easy. The basic requirements for recording involve accurately locating it on a topographic map or by GPS coordinates and photographing or drawing the images. Information, recording forms and instructions can be obtained on the recording sites page.

Where Can We See Them Now?

Web sites, such as are a quick and easy way to see petroglyph images from around the Commonwealth. There are also several museums in the Commonwealth that have casts of petroglyphs or the actual petroglyphs on display. The State Museum of Pennsylvania exhibits actual petroglyphs from Walnut Island and Cresswell Rock. The Pennsylvania Historical Commission "rescued" these in the 1930s prior to their flooding by dam construction along the Susquehanna River. A large number of petroglyphs salvaged from the Walnut Island and Cresswell Rock sites are also in the collections of the PHMC but not available for general viewing.

Also in Harrisburg, among the images of Pennsylvania culture and history depicted in the mosaic tile floor of the State Capitol Building, are seven petroglyph designs from Safe Harbor sites. The North Museum in Lancaster has six plaster casts made around 1900 of petroglyphs on Big Indian Rock.

Two rocks containing four petroglyphs salvaged from Walnut Island are on display at the Blue Rock Heritage Center in Washington Boro, Lancaster Co.

Four rocks containing ten carvings from Walnut Island and Cresswell Rock are on display at the Conestoga Historical Society Museum in Conestoga, Lancaster Co.

Indian Steps Museum in York County has small plaster models of Little Indian Rock and Cresswell Rock that were made as part of the 1930-31 Cadzow (PHC) expedition.

The Historical Society of Cecil County has four rocks containing six carvings salvaged from the Bald Friar sites in 1927 on display in an outdoor courtyard alongside their building in Elkton, MD.

The Historical Society of Harford County in Bel Air, MD has nine Bald Friar petroglyphs on display in the lobby of their facility, with two explanatory panels, a newspaper article, and a number of historic photos.

And the Jennings Petroglyph is on display in the lobby of Fahy Hall at Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ.

Many petroglyphs salvaged from the Bald Friar sites are presently housed Maryland Historical Trust's Archeological Conservation (MAC) Lab at Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum in Calvert County, MD., and many molds of, and documentation of western Pennsylvania petroglyphs are archived at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

Finally, a few sites are not on private property and can be visited. Indian God Rock is located on the Sandy Creek Trail, which is part of the Allegheny River Valley Trail system. The closest access point is at Coal City in Venango, County.

The sites at Safe Harbor can also be visited but require a boat, and ability to visit them is dictated by river conditions and knowledge of generation at the dam so care must be employed in these visits.

At all times when visiting petroglyphs in the field, they must be treated respectfully. These are sacred places to Native Americans. These represent a rare window into the cosmological minds of people who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago and they offer a glimpse into how people viewed the world around them. They are part of the heritage of all Pennsylvanians. Petroglyphs represent unique insights into past cultural behavior and they are a major contribution to our understanding of the past.

For Further Reading

The best books on Pennsylvania petroglyphs are Petroglyphs in the Susquehanna River near Safe Harbor, Pennsylvania by Donald A. Cadzow, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (2001) and Rock Art of the Upper Ohio Valley by James Swauger, published by Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria (1974).

Chapters on the Safe Harbor Petroglyphs and the Bald Friar Petroglyphs also appear in the book The Rock Art of Eastern North America - Capturing Images and Insight, Carol Diaz-Granados and James R. Duncan, Editors, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa (2004).

"Reading Rock Art: Interpreting the Indian Rock Paintings of the Canadian Shield" by Grace Rajnovich, Natural History/Natural Heritage, Inc., Toronto (1994) offers a fine introduction to the connection between historic Algonquian (Ojibway) ethnology and the interpretation of rock art symbols and sites.

"Picture Rocks - American Indian Rock Art in the Northeast Woodlands" by Edward J. Lenik, University Press of New England, Lebanon, NH (2002) is a landmark book that documents all the known rock art sites from New Jersey north to Nova Scotia.

"Rock Art of the Eastern Woodlands", Charles H. Faulkner, Editor, American Rock Art Research Association Occasional Paper 2, San Miguel (1996) is a compilation of thirteen papers documenting rock art sites ranging from the Midwestern to the Southeastern United States.