| PA State Archives | Hours, Directions, & Fees | Research Topics | Online Catalog | Land Records |

Click the following link to view the Canal Map Book Reference Guide.

The map books are for the most part unindexed. If searching for a specific place name, canal, region, topic, etc., use the Reference Guide to search for a particular topic (ctrl+F) or simply browse through the guide to see the contents of each book.

|

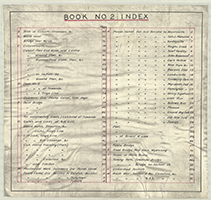

Map Book #2: 1836-1838. pp. 00-59 |

|

Map Book #3: 1830-1841. pp. 00-17 |

|

Map Book #4: 1824-1866. pp. 00-20 |

|

Map Book #5: 1828. pp. 00-31 |

|

Map Book #6: 1828. pp. 00-07 |

|

Map Book #7: 1827-1855. pp. 00-28 |

|

Map Book #8: n.d. pp. 00-22 |

|

Map Book #9: 1826. pp. 00-23 |

|

Map Book #10: n.d. pp. 00-36 |

|

Map Book #11: 1839-1841. pp. 00-37 |

|

Map Book #12: 1826-1827. pp. 00-22 |

|

Map Book #13: 1826-1866. pp. 00-06 |

|

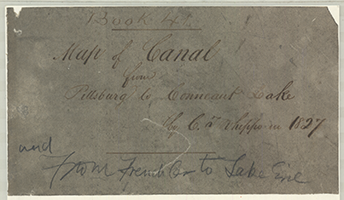

Map Book #14: 1881, n.d. pp. 00-02 |

|

Map Book #15: n.d. pp. 00-19 |

|

Map Book #16: 1831-1855. pp. 00-E |

|

Map Book #17: n.d. pp. 00 - c-2 |

|

Map Book #18: 1836-1846. pp. 00 - c-1 |

|

Map Book #19: 1824-1840. pp. 00 - k-8 |

|

Map Book #20: 1839-1840. pp. 00 - b-8 |

|

Map Book #21: 1826, 1839-1840. pp. 00-m |

|

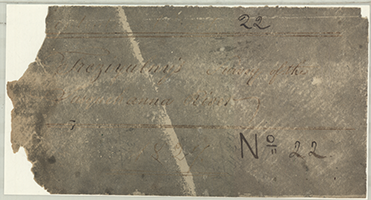

Map Book #22: 1827. pp. 00 - a-12 |

|

Map Book #23: 1825-1871. pp. 00-n |

|

Map Book #24: n.d. pp. 00-111 |

|

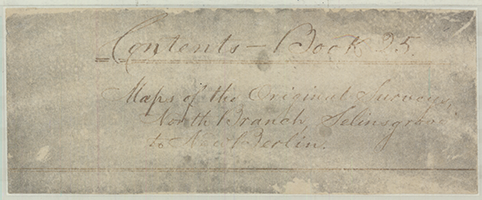

Map Book #25:1830-1831. pp. 00-d |

|

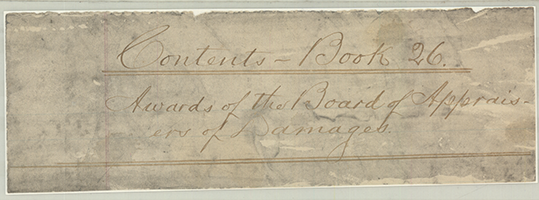

Map Book #26:1827-1835. pp. [not numbered] |

|

Map Book #27: n.d. pp. 00-No. 38; a-c |

|

Map Book #28: n.d. pp. 00-26 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #29: 1826-1833. pp. 00 - e' NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #30: 1836. pp. 00-29 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #31: 1826. pp. [not numbered] NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #32: 1840-1878. pp. No. 1-No. 13 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #34: 1828. pp. 01-18 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #35: 1828. pp. 1st Sheet-XIXth Sheet NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #36: 1836-1838. pp. [not numbered]-No. 17 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #37: 1810-1855. pp. [not numbered] NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #39: 1839, 1846, 1855. pp. a-g NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #40: 1828. pp. 01-03 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #41: 1827. pp. 00-c NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #42: 1828-1857. pp. [not numbered] NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #43: 1826-1851. pp. 00-39 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #44: n.d. pp. 00-No. 8 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #45: 1830. pp. 00-07 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #46: n.d. pp. Title Page Only (missing) NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #47: n.d. pp. Section XXXIX - Sections LXXVI & LXXVII NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

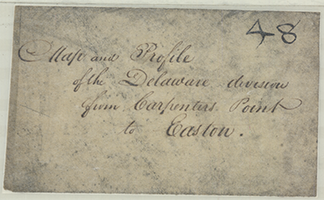

Map Book #48: 1827-1828. pp. 01-21 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #49: 1841. pp. 01-21 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

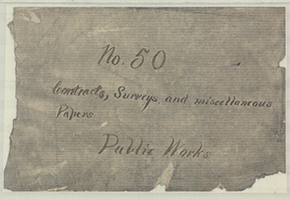

Map Book #50: 1836-1859. pp. 00-114 NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

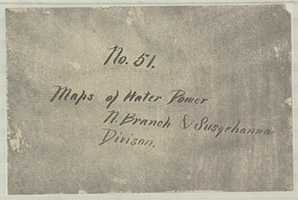

Map Book #51: 1841-1842. pp. [not numbered] NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

|

Map Book #52: 1841. pp. a-d NOT AVAILABLE ONLINE |

| PA State Archives | Hours, Directions, & Fees | Research Topics | Online Catalog | Land Records |